To awaken the multicultural memory of Kaunas city and towns in its district and remind of its rich history is one of the most ambitious goals of the project Kaunas – European Capital of Culture 2022. To achieve that, the program Memory Office was launched together with the project. Just in time for the grand opening of Kaunas 2022, the team behind the Memory Office published a book called “The Jews of Kaunas”. Dr Daiva Citvarienė, the curator of the program, reveals the reasons for the book and her personal relationship with Jewish Kaunas.

– “The Jews of Kaunas” could take the shape of a film or any other storytelling form. Why a book?

– Of course, a film of such kind could be made. I want to stress that the Memory Office, part of the Kaunas 2022 project, has already presented a handful of initiatives that highlight the Jewish memory of Kaunas, including a series of murals reminding us of the Jewish citizens that once lived in our city. I believe the book is one of the most important projects of such a kind. We started working on its idea right after Kaunas secured the title of the European Capital of Culture. Firstly, we wanted to fulfil the gap in the city’s history. Secondly, we found it essential to create a sustainable product that would not end after 2022. In this sense, a book is much more durable than an exhibition or a stage performance. It is our tribute to the people who lived here and helped build the city, to those that projected their future in Kaunas, and whose lives were so brutally terminated.

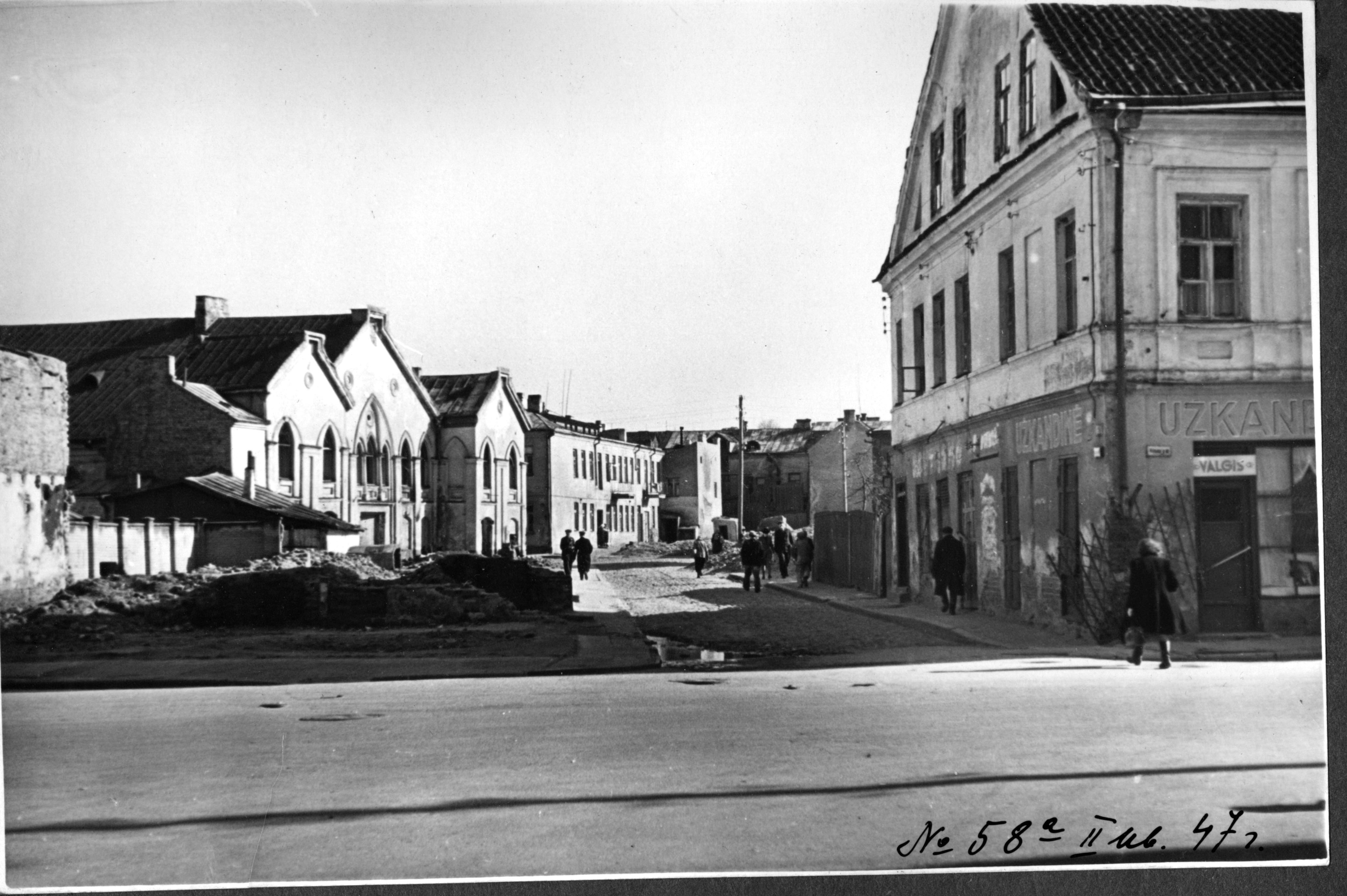

– The articles in the book are based on numerous sources and illustrated with historical documents, photographs, many of which haven’t been publicised before, even advertisements. Which findings that helped shape the book were the most surprising and touching?

– I can’t speak on behalf of other authors, primarily professional historians – they probably have a different relationship with iconographic material. I’m not a historian; therefore, I do not really care if a photograph was already published and how rare it is. The amount of history in the picture is much more vital for me and its capability of telling a regular reader more about a specific time, person, or event.

What really made me happy was seeing a picture of the pergola the Kaunas-born Hebrew novelist Abraham Mapu wrote in. I had read about the pergola numerous times, and this photograph helped me better imagine the stories I had found and the city in those times.

Another discovery was a collection of the burned-down Kaunas Ghetto. These were some of the most shocking images of Kaunas I had ever seen.

No less important than illustrations are the memories and testimonies of people that lived or visited Kaunas. These stories also help illustrate history. I am happy we could include quite a few memories about Kaunas at the end of the 19th–the beginning of the 20th centuries, found in English-language sources. These enriched the picture of the city we tried to create with the book. Another significant source was the stories we wrote down when talking to current-day Kaunasians, including Fruma Kučinskienė, Julijana Zarchi, Bella Shirin and others.

– The book covers some five hundred years, yet it’s just 200 pages. How did you concentrate the narrative – there must be something left for future publications, right?

– I find it essential to stress that we did not publish a book for the academic society but rather for the curious readers interested in history. It is by no means an encyclopedia. I see it as an introduction to the world of the city’s past, a world not much explored yet. We included some of the most important names and their contribution to education, culture, medicine, industry, business and other fields of life, as well as the painful pages of history. I hope the publication will inspire future research.

Regarding the form of the storytelling, it was essential for us not to make this a list of names and facts. In terms of building a relationship with history, I find what museums do very interesting. For example, in POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, the narrative is based on quotes, memories and testimonies. We use similar principles in the book.

I am positive that facts, dates and names are not enough to tell the story well. To genuinely understand how people lived 50 or 150 years ago, we need to comprehend how they thought, felt, and saw the world. That is why we have included numerous quotes and memories from historical sources. These inserts are witnesses to time, adding life, breath and colour to the big picture.

– Did you encounter many contradictions in various sources? Is it easy to pick the most accurate truth when many event witnesses are not alive anymore?

– The research of the history of Kaunas Jews is still quite fragmented. We compiled the book together with historian Arvydas Pakštalis and aimed to collect what’s already done in the field, connect the stories, and fill some gaps. Arvydas is a keen visitor of archives, and he managed to correct some of the statements that have been floating around for some time now. On the other hand, I am sure that new facts and discoveries will appear after the book is out, and some more corrections might need to be done. I think it’s a natural process as the history of Jews in Kaunas is just beginning to be written.

– In recent years, we lost quite a few bright people necessary for the context and content of the book, namely Leonidas Donskis and Irena Veisaitė. Do you feel you didn’t have the chance to interview some personalities?

– Sadly, we dedicated the last pages of the book to those that left us too early, both Leonidas and Irena. It’s a pity we didn’t discuss the book with Irena when we still had the chance. And, when working on the text about Leonidas, we realised how little we know about the history of his family. Still, we found it extremely important to include stories about them and other contemporary Kaunasians and to stress that the Jewish history in Kaunas is still alive.

– The author collective is impressive. What was the book writing process like?

– Arvydas and I first collected what was already out there. The hard part of the job was connecting the fragments into a narrative; this is where Arvydas stepped in and filled the gaps. My task was to represent the reader and raise questions answers to which might seem obvious for a historian yet not always clear for an average citizen. I found it meaningful also to present traditions, culture and even the language – we decided to include a glossary.

– If someone decides to dig deeper into a period, a family or an event described in the book, which choice would make the Memory Office the happiest?

– As I’ve mentioned, these are only the first steps of the research of Kaunas Jews. The book could have been three times thicker! I hope some of the names we could not include will be remembered and researched by other authors. We’ll appreciate every initiative to revive the history.

– What were the first reactions to the book?

– The Kaunas Jewish Community knew about the process from the beginning, and I believe they were looking forward to reading the book. For us, it’s not just a tribute to people who lived there, but also a gift to the members of the community that became our close friends. For many of them, it’s a meaningful sign showing that their history and community drama are not forgotten.

– Can the book cause pain?

– It is painful for everyone that understands the size of the tragedy that happened in Europe and our city during WW2. Looking at the prewar photographs and understanding what kind of faith awaits the smiling people in them simply brings tears. One understands how much we lost by telling the beautiful stories of people who contributed significantly to building Kaunas. What’s hard to comprehend is how it could happen.

– Along with documents and photographs, the book is illustrated by original drawings by Darius Petreikis, who also created the Beast of Kaunas. How do the pictures enhance the texts?

– We did not aim for a traditional book full of facts and documents. We wanted it to cause curiosity. History can be fascinating, and it can be presented playfully. We’re speaking about a period of several hundred years about the community’s culture, traditions, and customs. We wanted to tell that story lightly, with a pinch of humour. After all, Jewish history is not just about the Holocaust. It’s so much more, it’s centuries of culture, traditions, customs, and it was important for us to remind that.

– Will the English version of the book become a meaningful souvenir from Kaunas, the European Capital of Culture?

– Indeed, the audience of the book includes Litvaks of the world and everyone else interested in the history of our region – this is why we prepared the English version, too. On October 29–30, the World Litvak Forum will take place in Kaunas; the Memory Office will invite everyone to more than 20 events dedicated to Jewish memory, including exhibitions, concerts and performances. I must also mention That Which We Do Not Remember, an exhibition by William Kentridge, one of the most famous Litvak artists, that will be displayed through 2022. Our book will be a meaningful bonus to the extensive programme and, yes, a meaningful souvenir.

– Daiva, please share some of the places in Jewish Kaunas that are the most important for you and still preserve its aura.

– I discovered the Jewish Kaunas some five years ago when working on an audiovisual route called The Spirit’s Guide to the old City. Looking for interesting objects made me stop in front of buildings I used to pass by every day and try seeing what’s not always apparent from the first glance.

I believe the Jewish Kaunas is still something hidden. Many signs of history have already disappeared or become unnoticeable. For this reason, the Memory Office initiated the creation of new murals inspired by old photographs and representing forgotten pages of our city’s history.

Speaking of the aura, one of such buildings for me is the current Kaunas Musical School No. 1 on J. Gruodžio St. In 1905, Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan Spektor established an orphanage in this building. Amazingly, you can still see the traces of old writings on the facade. Also, my son learned how to play the piano there, which I find pretty symbolic.

Another location essential for me to is my birthplace, the former Jewish hospital on A. Jakšto St. I am looking forward to seeing it alive again. Last but not least is the Kaunas Choral Synagogue, one of the most beautiful examples of Jewish sacral architecture, still waiting for its new golden era.

Places no longer identified as Jewish or not remembered as such are also very important. Among those are the J. Naujalis Music School (former Jewish Realgymnasium), VMU Law Faculty (Former ORT School), the former house of doctor Elchanan Elkes on Kęstučio St. or the New synagogue on Birštono St. which today is a car repair shop. I could also elaborate on the Old Town and Laisvės alėja, full of former bookstores, shops, barbershops, cinemas and restaurants established by Jewish businessmen. We must remember and remind this page of the history of our city.

Kaunas and the surrounding Kaunas district are ready to become one big European stage next year, offering over 1000 events. More than 40 festivals, 60 exhibitions, 250 performing arts events (of which more than 50 are premieres), and over 250 concerts are planned to take place in 2022. All this is delivered by Kaunas 2022’s team of 500 people, alongside 80 local and 150 foreign partners. 140 cities in Lithuania and the world, 2,000 artists, 80 communities, and 1,000 great volunteers.

Full programme