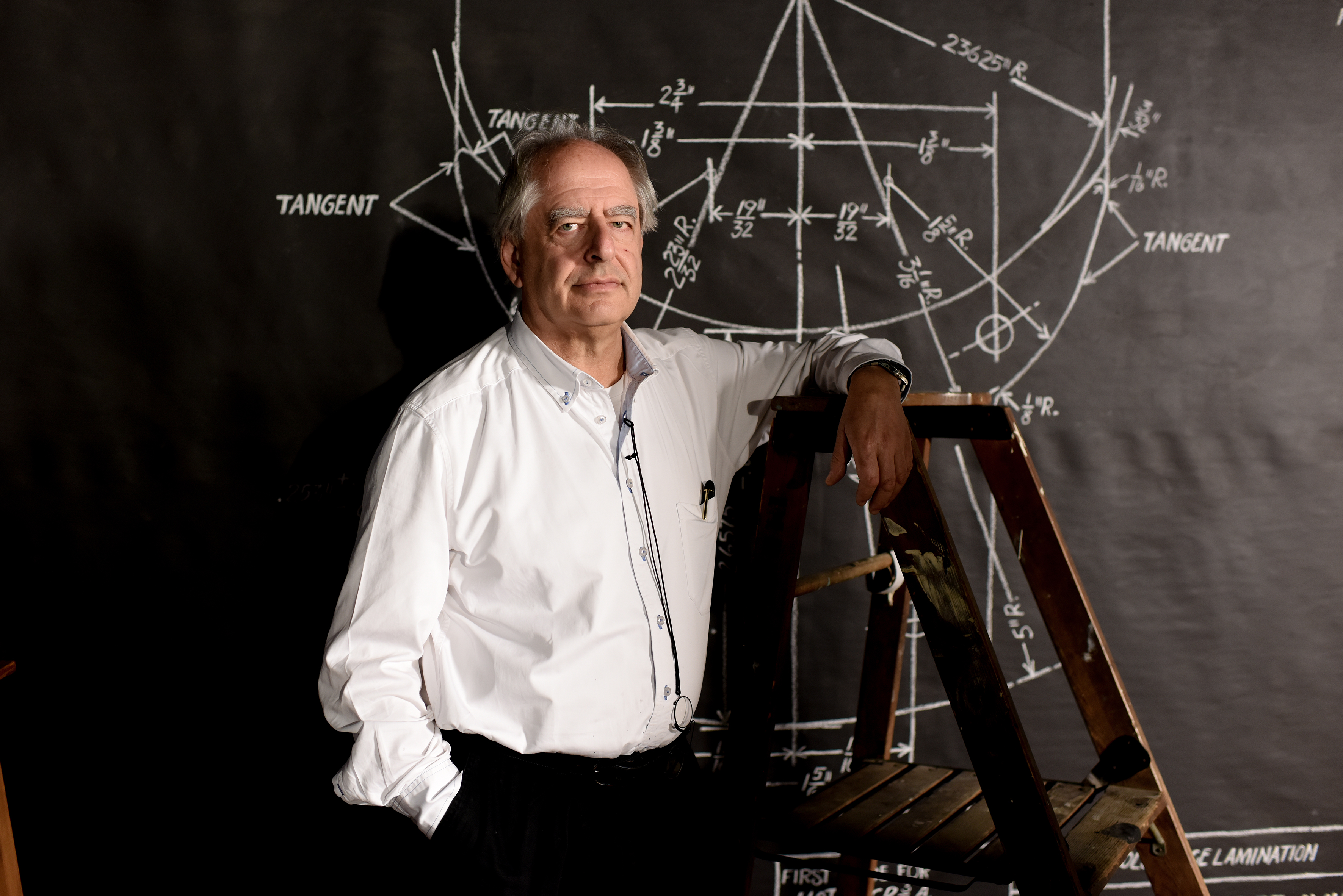

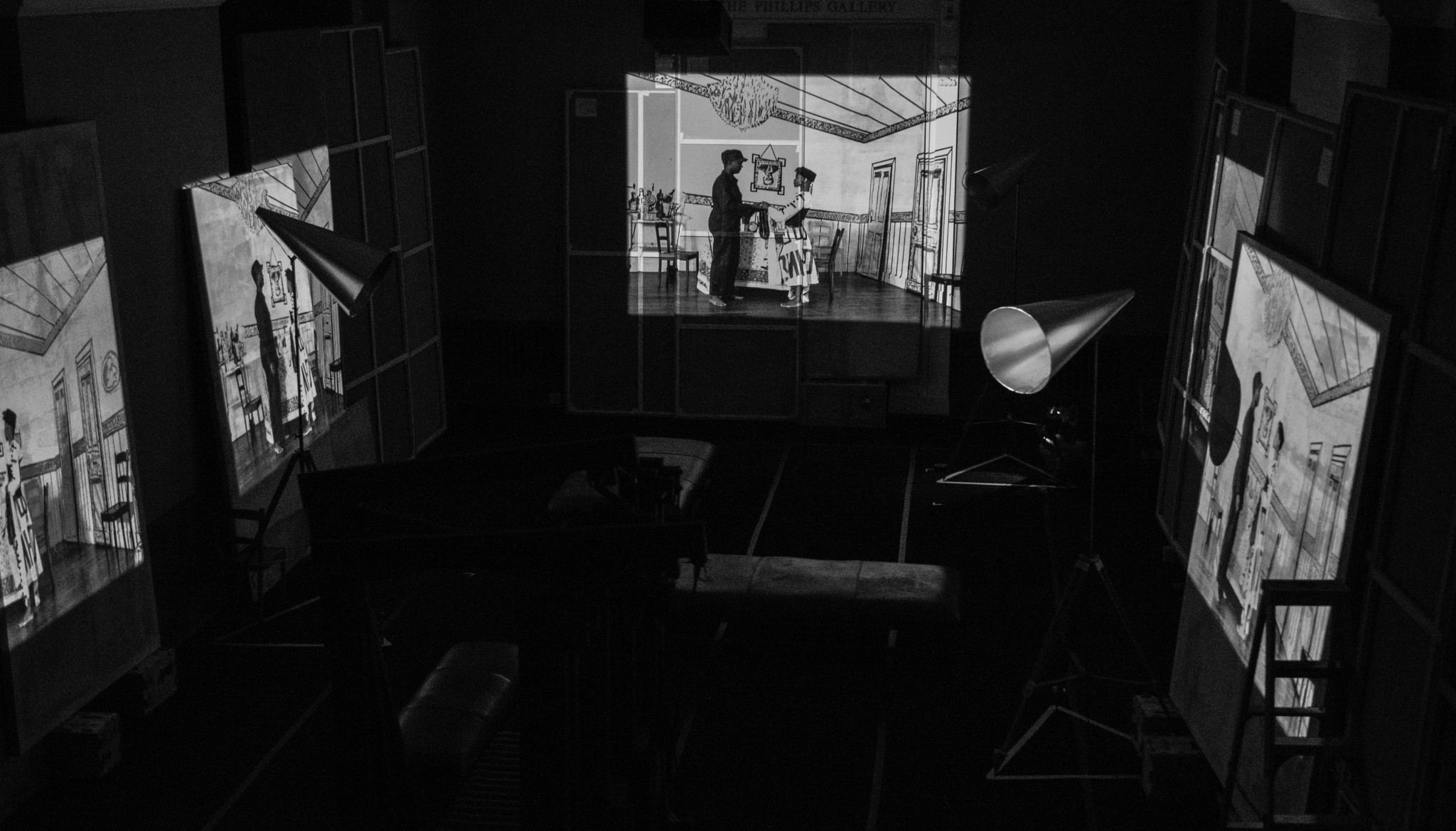

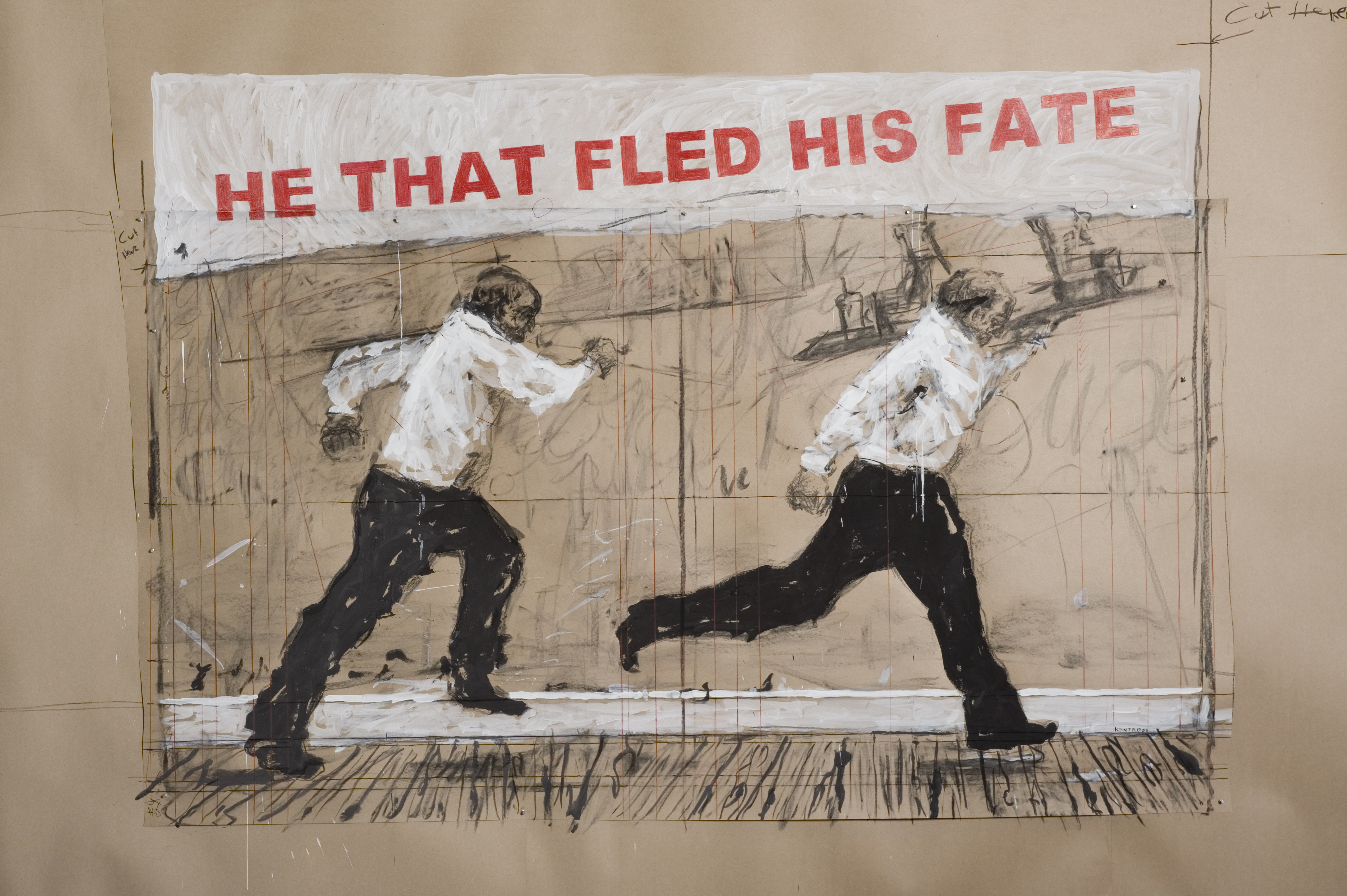

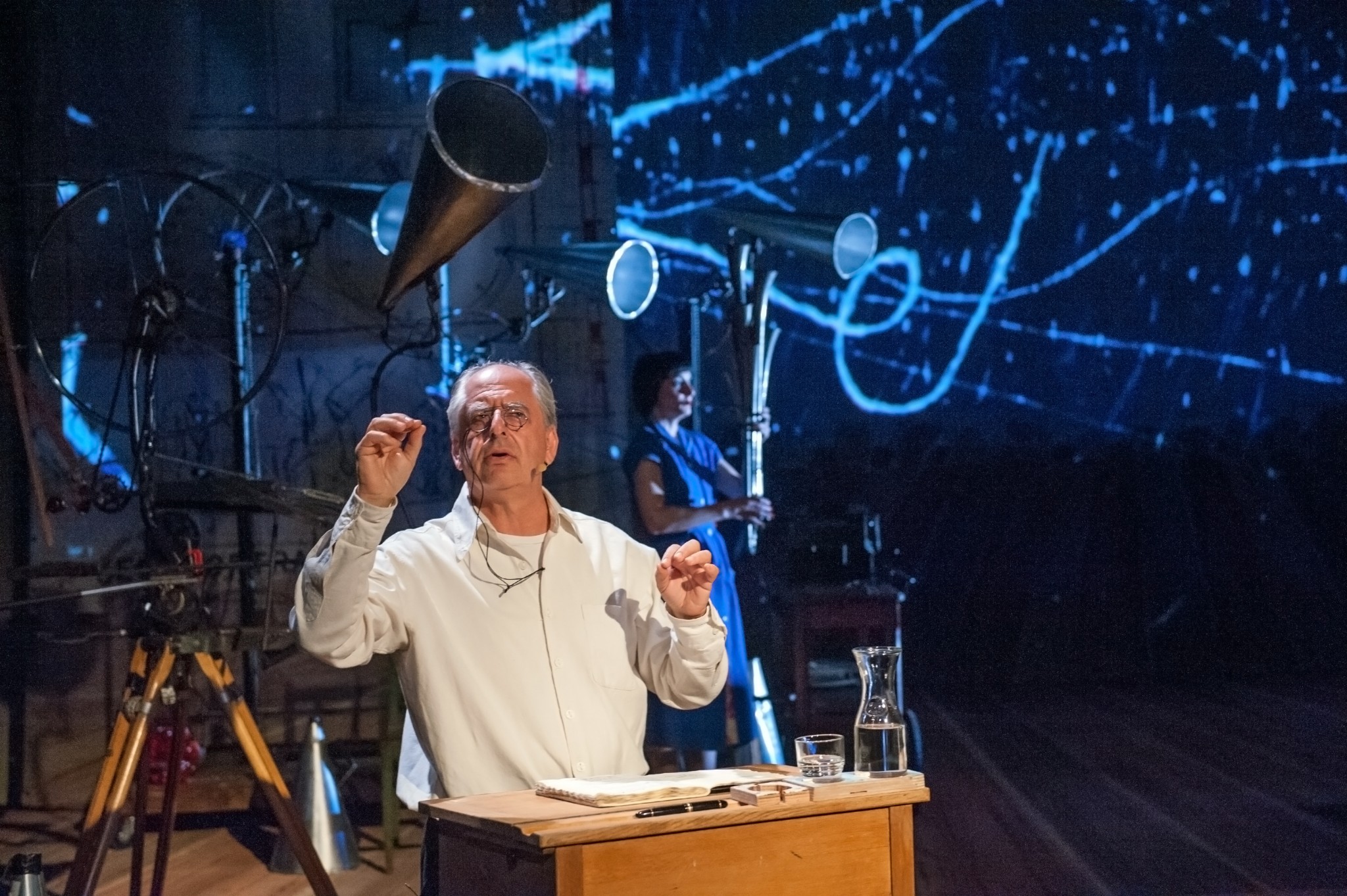

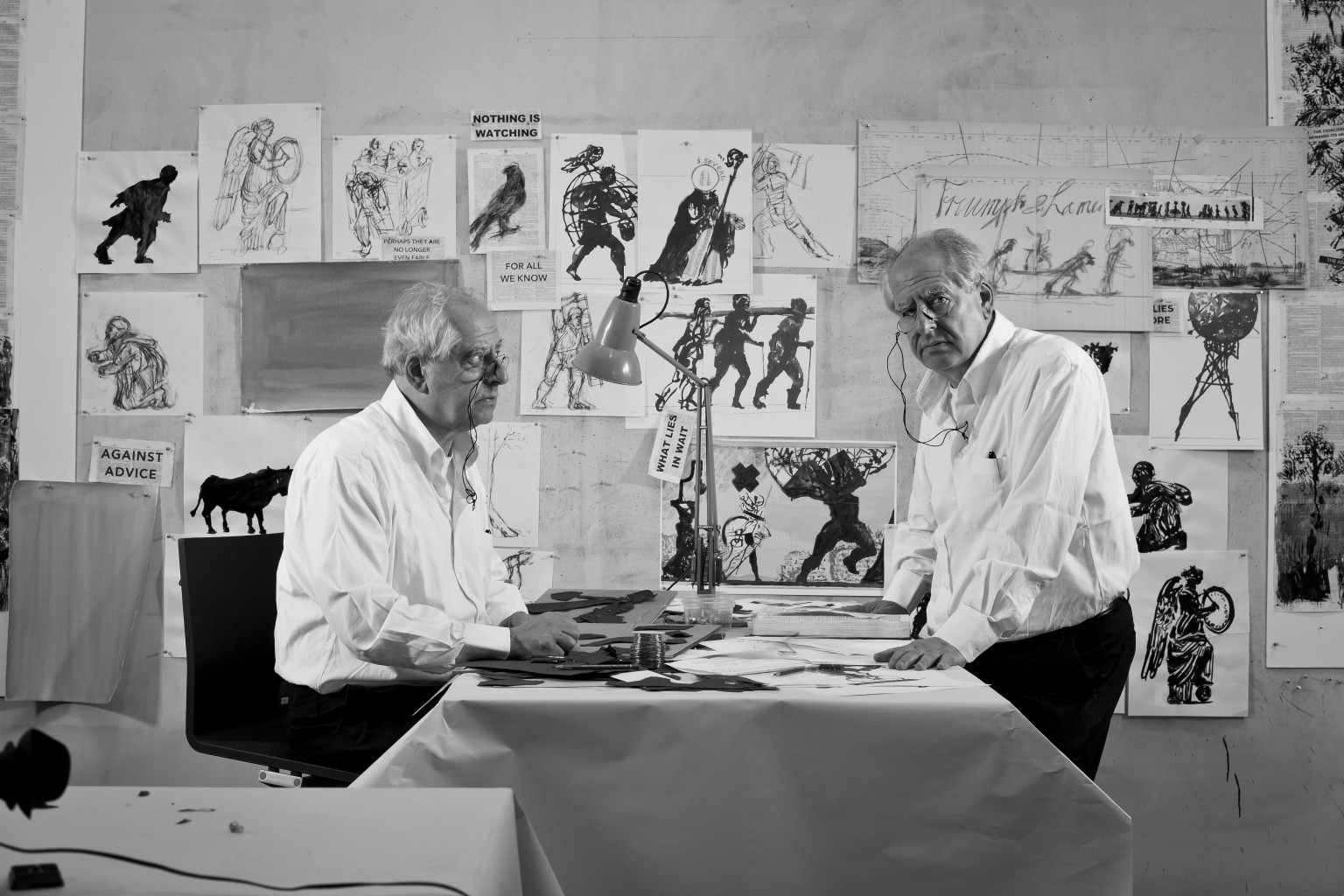

William Kentridge’s grand exhibition (curator Virginija Vitkienė) That Which We Do Not Remember, which will take place at the National M. K. Čiurlionis Art Museum, should be noted as one of the most important events in next year’s “Kaunas – European Capital of Culture 2022” program. Born in South Africa, in Johannesburg, in 1955, the artist with Lithuanian roots has been known and honored in the arts for many decades, and his works have visited the world’s most important galleries and become part of large collections. Kentridge is an intellectual who provokes emotion and reflection. His sources of inspiration range from science to literature, and his artistic means range from charcoal drawings, paintings, textiles, animated films to opera productions. This reflects the author’s own educational spectrum and wide field of interest.

– You studied a lot yourself and you certainly had great teachers. Are you a teacher yourself?

– My wife likes to tell the story about Jewish husbands: they never leave you but when they turn fifty, they become rabbis. So sometimes I think I have become a 66-year-old rabbi. And in the context of The Centre for the Less Good Idea, a lot of what I do is in a role of teaching.

For years when I was asked to teach, I thought, well, I’m still learning, I’ve got nothing to teach. Now I feel I’m still learning, but I do have something to teach. And more than that, often I learn from working with the younger artists.

There’s been enough experience in the studio; sometimes now I am able to respond to the misery of the anxieties that younger artists have, and which I had when I was much younger. Not that there aren’t anxieties now, but they are different anxieties, they’re not those of a young artist.

– What gives you the courage to create?

– The activity of continuing with work day after day, whether you’re a writer or a painter, is hard when you’re starting. I think that requires more courage than it does to keep going when you’ve got a trajectory and a momentum, and an experience of projects having worked out in the past.

When you’re starting out, every new piece is vital. If one drawing or one painting seems to disintegrate and be not worth it: is this telling me the truth about who I am? I’m doomed for things to fail! So, to get past that is a kind of artistic courage. It also takes a mixture of obstinacy, stubbornness, thick-skinnedness to not mind the responses of people to one’s work if they don’t like it. This is never something that I’ve been able to do.

I think to be an artist is so much about a psychic lack, a gap. This gap is feeling that in yourself you’re not enough. You have to leave this trail of objects and things behind you for other people to see, so that you can see yourself, looking at these objects. It’s not about courage, it’s about inadequacy.

– What connection, if any, do you see between originality and authenticity?

– Authenticity as a starting point doesn’t interest me. I’m interested in what emerges through the process. I’m more interested in stupidity, or another way of saying that: giving the whim, giving a quick idea, the benefit of the doubt and seeing where that leads us.

The vast majority of the projects I’ve done, and the discoveries which have been interesting to myself or to other people, have inauthentic origins. You start from thinking of one thing and then you’re following one idea, and then something else emerges. It’s not that a clear thought and a clear line of investigation lead to an answer to a question you’ve asked yourself.

– In our works one can notice a lot of negativity, reversing, negation. Is this your artistic tool? What does this mean for you?

– I’m interested in the negative in the photographic, metaphoric sense. The negative is what is recorded on that piece of film from which we make a second negative, which is the positive print.

You film the ants on a sheet of white paper moving around in their different formations and then invert: the white paper becomes the night sky and the black ants become spots of light in the night sky. You’ve made a herd of moving stars and planets.

That’s the practical sense of the negative, which is not the void, but it shows the explanatory power of darkness – rather than assuming, from Plato onwards, that everything has to do with light as an explanation, that one has to bring light to darkness to understand. Sometimes one needs that strange mixture of darkness and light for things to make sense.

A black hole in space as a place of massive gravity that will absorb all light and anything that it swallows. That finality. Of course, in understanding physics I am trying to make sense of our own black hole, a six-foot grave that we’re heading into, that void. If you can’t bear the thought of the finality of that void, you need to believe that something can still emanate from that darkness, in which case one believes in a soul.

– Quite often you involve entropy in your work. What is it?

– The artist’s job is to resist entropy. If you throw a vase up, it shatters on the ground. If you pick up all the shards and throw them back into the air, it’s very unlikely that they’re going to reform exactly as the intact vase was before it was broken. It’s that statistical improbability, which is the basis of entropy, of something that is ordered breaking down into a state of disorder. The artist’s job is to take those fragments, the shards of the vessel, those torn up pieces of paper, and reconstruct something new, a new image. The form is of collage, but it’s a different way of saying that we construct our understanding from fragments that we pick up all around us and inside us. That battle against entropy – and the fact that in the studio this is a battle that we win every day – makes entropy an important and good category to work with.

– What is your relationship with tradition?

– I am interested in mistranslation, in imagined context, rather than deeply understood context. I’m skeptical of an art of identity and the politics of identity, but rather interested in the politics of bastardy, of hybridization, of resisting tradition and believing also that most traditions are invented and constructed. Certainly, in the colonial world, the work that was done by the colonial administrations was to invent the tribes, the cities, the clans, the tartans of Scotland, to understand those as constructions rather than as things to be discovered.

We have to be aware of tradition, because even if we deny it, our eyes and our brains are constructed through all the things we’ve heard, seen and been told. Our eye sees differently to the way anyone’s eye has seen in the centuries before us.

– Could art be called the best tool for creating narratives of history?

– We have to understand different forms of constructed ignorances in which things are deliberately hidden from us, histories are hidden from us, archives closed, shameful facts burned. I think one of the things that I’m aware of now is needing to give more attention to the periphery, to the things which one puts in the side cabinet. To take them out again, look at them again.

Because of art’s way of working with fragments, of constructing meaning through collage, is that we can construct other narratives, and narratives of history as well, by putting together different fragments. So, what is a natural process in the studio – taking a fragment from one drawing, a detail from a photograph, constructing an image from these different fragments – is also a model of how we can think of history.

– Your upcoming exhibition is of impressive scope and will be given special attention. You have not visited Lithuania yourself yet. What is your personal relationship with our country?

– I’ve always thought of myself as being of that part of South African Jewry, the Litvak – people who came from Lithuania (which is where most South African Jews come from). But I’ve never been to Lithuania.

My grandfather in his autobiography only gives one sentence to the place where he spent the first several years of his life. He simply says: I was born in Lithuania, from which many South African Jews come, I left Lithuania and went to England.

I have no sense of Shtetl life, of my ancestors’ life in Lithuania. I have no wish for restitution, certainly not of retribution, of thinking that I’m owed anything by Lithuania.

Eleven years ago, my daughter visited Lithuania and found almost no acknowledgement of what had happened there. I’m interested to come to Lithuania to see how it feels and whether my imagined country and its history corresponds to what I find when I am there.

Kaunas and the surrounding Kaunas district are ready to become one big European stage next year, offering over 1000 events. More than 40 festivals, 60 exhibitions, 250 performing arts events (of which more than 50 are premieres), and over 250 concerts are planned to take place in 2022. All this is delivered by Kaunas 2022’s team of 500 people, alongside 80 local and 150 foreign partners. 140 cities in Lithuania and the world, 2,000 artists, 80 communities, and 1,000 great volunteers. The Official Opening ceremony 22th, January, 2022.

Full programme: www.kaunas2022.eu

Interviewed by Sandra Bernotaitė