As Margarita Štromaitė wrote in her memoirs, during the Second World War, the lives of her, her future husband Juozas Kaganas, who she met in the Kaunas ghetto, and his mother Mira were saved by the family of Vytautas Rinkevičius. “<…> in spite of the mortal danger that threatened his entire family he built and equipped a shelter for us in the attic of the foundry. It was made in a part of the ridge separated by a false wall.” It was not until twenty years after the war that Margarita met her only relative who had survived the Holocaust, her brother Alexander Shtrom. In 1965, Margarita and Juozas, already known as Joseph had a daughter, Eugenia. Or Jenny.

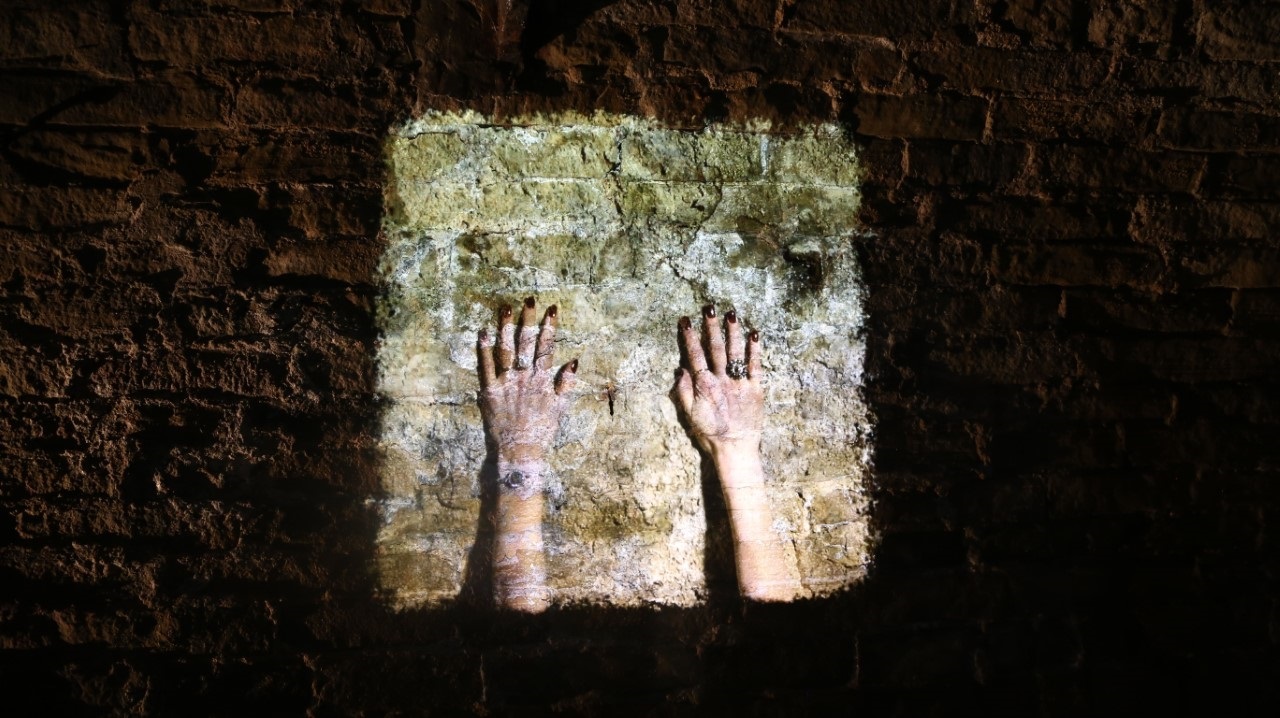

Jenny Kagan presents the exhibition “Out of Darkness” in Kaunas, the European Capital of Culture, from 4 August. With sensitive artistic solutions, texts and sound, she reveals her family’s poignant story, at the same time uncovering the unknown pages of Kaunas’ memory. Nevertheless, it is a story about humanity and the light necessary for our survival as a civilisation. The exhibition at Gimnazijos St. 4 is part of the CityTelling Festival initiated by Kaunas 2022. The artist, who previously worked lighting designer in the theatre for many years, has agreed to tell us more about her creative journey.

“Out of Darkness” in Kaunas was announced a few years ago already. Did the past pandemic months influence the exhibition?

Securing a building took a lot of time – the one on Gimnazijos St. is the third one. In the first one, we couldn’t negotiate a deal with the owners that would work. I had already prepared a design… I visited Lithuania during the pandemic because my aunt Irena Veisaitė died. It was December 2020, and I also wanted to see the second building the team found. It wasn’t anywhere near as good as the first one, but by that point, I was like, “We have to start.” I went away and designed the show for there. I made a model and did it all. Then the owners withdrew… And this building came up, and last summer, we finally were certain we had it. The show is very much about the venue.

The building is close to the synagogue you worked in during the Kaunas Biennial.

I know! My mom went to the school over the road, and my grandfather lived a few hundred yards away at one point, so it’s a really great location. Its owner is an amazing person. They asked me, which bit of building I would want to use, and I asked for all of it. There is no way to get between the spaces on the ground floor of the building, and there are no stairs to go upstairs. I came up with this crazy idea to build corridors to connect the parts. We decided to build these scaffolding corridors so we’ll use all three parts and you’ll come out and into the car park and along a corridor and then onto the street into a corridor and then into the other building so it’ll be quite an adventure. I’m banking on the fact that it’ll be so interesting just going to the building; it doesn’t really matter if the work is not fabulous (laughs).

But really, it does help. When I did the show in the UK in 2016, the building was half of the atmosphere. It’s just exciting to go somewhere and explore it, so you start on a win.

How much of the content has changed since 2016? Maybe you have made some new discoveries or some new artistic work?

Loads and new loads of it have changed. It’s changed much more than I ever expected it to. Some of it was because of the restraints of the building. When I did it before, I did it in an old theatre, so a lot of things were based on things hanging because there was a grid everywhere. Here, the owners said we could do anything to the building but couldn’t hang anything from the ceiling.

Can you tell us more about the genesis of the show?

The show initially consisted of three central pieces. It all started with my mom, as my father had already passed away. Both my parents always used to talk about their time in the shelter, in the box. The box was the family story.

About 12 years ago, I stopped doing theatre and did a drawing degree. I had to do a project, and I asked my mom, “Why don’t we draw the box together?” Because she’d always told me stories of it. When I was a kid, I imagined it as a toy box, but when I got older, I went to the Anne Frank House and saw this apartment. I thought, “Oh, this is what a hiding place looks like.” Much later, I talked to my mom a bit more and realised that it was actually closer to my first imaginings, so I said, “Why don’t we draw the box so we can visualise it?” We started to do that, and I couldn’t draw very well. She’d look at these drawings and go, “Oh, I didn’t know.”

At that point, I started to make little models and bring them to her. She’d say, “Oh, it’s a bit bigger, and the bed was here,” and so we did that. Then I built a mockup, and she walked in and said, “The door’s on the wrong side.” So, I made a replica of the box for my college project. She came to the final show and said, “It’s great, but still a little bit too big.” I guess I was always trying to make it bigger because I couldn’t believe it was really that small.

The local museum wanted to exhibit that summer, but it wouldn’t go through the door. I took another 6 inches off it. Mother came to see it and said, “Now it’s a perfect size.”

Two years later, my mother died. I wanted to continue working with the piece, as I’d never really got to grips. I’d got the box size, but I didn’t really understand where it was in the building and how it worked. I went back and looked through all my father’s papers to see if there were any more descriptions, and I found his description of it, and in his version, it was slightly different. I thought that was really interesting, and then I built his version.

So in the show, there’s his version, her version, and my memory of the toy box version. That was what the show was built around there. This and the idea of memory not being something fixed was the first foundation. The three hiding places are slightly different in Kaunas, but they’re still there.

Then the second linchpin was the Big Action. I was born on the 28th of October, so this was always a big thing for my mom. I always wanted to do work about Big Action. It was always about being sent to the left or the right and about getting people to feel in a very visceral way how delicate that moment is and how easy it is for it to go in either direction.

I built this maze which had three stations. There’s a Jewish game, dreidel. There were dreidels that you spun, and you would go either to one side or the other through this maze of barbed wire. That piece would not work in Kaunas. I spent a long time trying to squeeze it in, and then I realised I just had to change it. It’s turned into a games room, but it’s the same idea. It’s about that feeling of chance and that it could go either way at any time.

The third piece, central to the show, is the starscape of barbed wire, which is very beautiful. I wanted something uplifting because it’s a hard story to tell. Ultimately, my parents survived, and ultimately, it’s a love story. In the Kaunas version, the starscape of barbed wire is still there, but finding a space for it was really tricky. It’s smaller, and I hope it will be extraordinary.

It was very important for me to have something that people could enjoy. I know it sounds crazy, but all the way through, I think that if you’re going to ask people to listen to this story, you need to give them a way to enjoy the experience. It’s important to me to talk to young people and for them to engage with it. So the games room felt like an excellent idea.

I am thinking about the legacy of Anne Frank. Recently an animated film by Israeli director Ari Folman came out, which features Anne’s imaginary friend, and I believe this is the right way to connect to younger audiences. The youngest ones, which is crucial.

Yes. The thing I implemented this time that I didn’t do last time is talking about the Lietūkis massacre because my grandfather was killed there. It doesn’t mean anything in England, but here I’ve been struck by how few people know about it. I met a bunch of people working on the show, who are all educated, interested people in their 30s and 40s, all living in Kaunas, and none of the three had heard about it.

Telling that story is really hard and really important. A lot of my thinking has been around how to do that. My grandfather owned a cinema called Pasaka, and we reconstructed its neon sign for the show. When I realised ‘Pasaka’ means’ fairytale’, I was like, “What a gift!”

Have you been inside the cinema, which today is a gentlemen’s club?

No. I go past it. I have a new piece at the end, which uses photographs. When I was a kid, my mom had a photo album with family photos, and on the back page were two photographs of Lietūkis. A German paper newspaper in the ’50s published photographs, and she got copies and put them in a family photo album.

Of course, the other big new thing is that I’m working in two languages. Anything that’s a challenge produces something interesting. There’s also more sound, as we now recorded pieces in both languages. There used to be too much to read in the first show, and there’s still a lot! There are many books in the show that you open, and the rule is you should be able to read it all in 30 seconds because I think that’s people’s attention span. It’s just about giving people enough context so that the pieces make sense. Some people will spend hours reading every word, and then others won’t read any of it. That’s fine. It’s designed to work for however you engage with it.

Isn’t that where your years of experience in theatre production come in?

I would say it’s like a theatre without any actors. I don’t know how a Lithuanian audience will react. In England, first, we had all these suitcases you can open, and the first audiences didn’t touch them. In the end, I wrote on them, “Open me.” Then people went for it. It’s about finding out how much I must tell people to do so; there are drawers to open and telephones to pick up. Will people pick up the phone if it rings? Will they open every drawer? That’s a voyage of discovery, and I’m sure I will keep changing things. Also, I’m going to work quite closely with that team. Hopefully, they’ll be able to encourage people to interact.

When you first started sketching the box with your mother, could you imagine that in 12 years or so, you would be opening an exhibition in her hometown? What were her feelings about Lithuania? Did she come here after the war?

My mom came regularly. I came with her. She shared an outlook on life that one can’t judge. One can only judge people who commit acts, not anyone around them, and it’s people, not nationalities. One of the many stories she told me and wrote down was about going to the European basketball final in 1939, for which the sports hall was built. When Lithuania beat Latvia, she writes about how horrified she was that the Lithuanian audience was booing the Latvian players. It’s so her. She was 16. That’s the golden diary entry for the first entry. It tells her position really clearly. There’s another story about after they come out of the ghetto and the Germans were retreating. She was walking down the road with a friend, and a German soldier was sitting. They walked past him, and her friend was smoking. The German said to her friend, “Have you got a cigarette, mate?” Her friend looked at him like the soldier was the dirt on the bottom of his shoe. She was horrified, her entire family had been killed by the Germans, but, she said, this was one man, and all he wanted was a cigarette. That was very much her outlook. That man hadn’t done anything necessarily.

Do you share the same outlook?

I think it’s the only way to go forward.

Have you ever thought about what would have happened if your parents had stayed in Lithuania?

I never have.

I think even your name would be different.

Actually, I’m named after my grandmother Eugenia, so Jenny is an abbreviation of Eugenia. It first became Jenia, and then it became Jenny. I think it would’ve been different because my parents would’ve been very different. My father was extraordinarily successful in England, and I think he probably would’ve been successful wherever he was. Maybe he’d have been accepted more here, in Lithuania. He was always the jumped-up Jewish emigrant in England who got above his station.

He wanted to be accepted into the high echelons of British society and eventually became a Lord. You’d think that was it, but he recognised it was his great sadness that no matter how much he achieved, he was never quite going to be part of that elite that he hankered after being part of.

My mom, she had never been to England. My father was already living there before the war, and his family were in England. After the war, he wanted to go back to England. Her only surviving relative was her little brother Aleksander Shtromas, who was in Lithuania. She needed to stay here. The thing that tipped her into going was that, once she found out about Lietūkis. How to live in a city, where anyone walking past on the street might have killed your father? That’s what encouraged her to leave.