Jon Hendricks is one of the originators, researchers, and curators in the history of the Fluxus movement. He is the curator of the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection. This essential collection of the Fluxus art movement began to be compiled in 1977 and was later donated to MoMA in 2008, where it is currently housed. A small part of the collection is exhibited in the George Maciunas Fluxus Cabinet at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius. Hendricks organized a host of major important Fluxus exhibitions and produced pioneering scholarly publications on the movement.

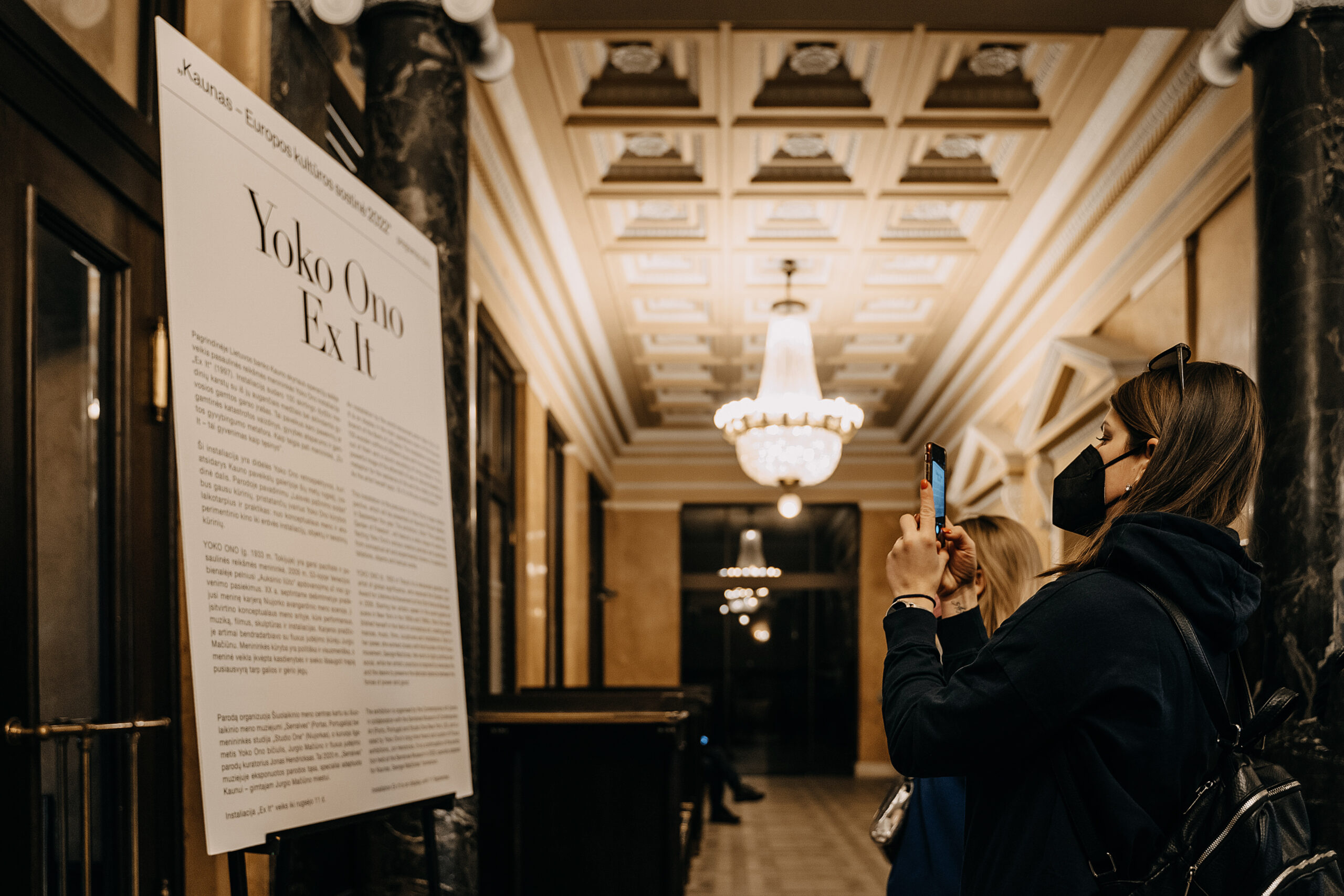

Jon Hendricks is also the curator of Yoko Ono’s retrospective exhibition The Learning Garden of Freedom, opening in Kaunas this year in September.

The Fluxus art movement was crucial to the radical shift in the understanding of art in different parts of the world starting in the sixties. Fluxus manifestos, numerous artworks, and instructions on how to make them circulated intensely for many years among artists in the United States, Europe and Japan, in a network coordinated largely by the founder of the movement, architect and designer George Maciunas (Jurgis Mačiūnas), a Lithuanian émigré. Having originated in New York, the movement was directed against the rigid, elitist and ‘overly self-important’ artistic system of art schools, museums, and concerts of “serious” music, which refused any kind of levity, spontaneity and play. Yoko Ono began her artistic journey together with the Fluxus artists. You started your career as an artist.

You learned about Fluxus at the very beginning of the movement and eventually got involved as a curator and researcher, still having close links with it to this day. How did it all start and what attracted you to Fluxus?

It was a radical movement, and it was precisely its radicalism that got me fascinated. I found out about Fluxus quite early. By the way, my brother Geoffrey Hendricks was one of the Fluxus artists. At that time, I already knew other artists from the movement. But my deeper interest in it began in 1976, when Barbara Moore and I opened the Backworks bookshop. I didn’t have a job back then and the bookstore first opened in my house. We were selling contemporary artists’ books, publications and Fluxus works.

We ran the bookshop ourselves, but as you can guess, it didn’t bring much profit. Barbara and her husband Peter Moore were well acquainted with Fluxus. Peter was an important photographer and was also capturing Fluxus performances. They knew George Maciunas, who agreed to sell his Fluxus works, and we helped him. Thus, I became friends with George as well. Around the same time, Gilbert Silverman invited me to curate his and his wife Lila’s Fluxus collection. I was afraid that working in a bookshop and curating a private collection at the same time might cause some conflict, so I chose working on the collection. Gilbert was a very progressive and adventurous collector. Together we assembled a very large Fluxus collection, which is now housed in MoMA. For multiple reasons, this collection is now considered the most important Fluxus collection of all. That was the beginning of my involvement with Fluxus.

You collaborate with Yoko Ono (b. 1933) and curate her exhibitions to this day. Tell us about your experience of working with her.

I met Yoko Ono a very long time ago, maybe in 1965 or 1966. I curated an exhibition of hers, titled The Stone, when I was working at the Judson Gallery located in a functional church of the same name. Later Yoko left for Europe, and I didn’t see her for quite a while, but when she came back our friendship continued. Working with Yoko is an incredibly wonderful experience. She is very ingenious and has a very special way of thinking. She would come up with new ideas in a flash. For instance, she was invited to participate in an exhibition in Finland related to snow and during dinner she immediately had an idea for an artwork: ICE PRISON. Melting ice liberates. She is very quick to have great ideas.

Yoko Ono’s work, related to social and political activism, touches on freedom, equality, women’s rights, and other topics that were used to promote society’s awareness. How do you see her work is presented to society today? Why is it important to get to know Yoko Ono’s work today?

It’s really a pity, but nothing has changed since her works were created and presented for the first time. Of course, there has been some progress in terms of women’s rights. But we still have a very long way ahead of us. And we can even feel it in our daily lives. When women walk down the street, they hear men whistling at them, not to mention the violence that women experience every day. One example is Yoko Ono’s piece ARISING which she first presented in Venice, with a bonfire made from a moulage of women’s bodies later lit in the centre of the piece, displayed together with a collection of real testimonials of violence and abuse experienced by women. I think this work is very powerful and we have shown it many times, continuing to collect further testimonials. This piece is no less relevant today.

The artist’s installation Ex It, now presented in Kaunas, features 100 coffins of different sizes with pine and birch trees growing out of them. Why are you starting the presentation of the artist’s work with this particular piece?

The installation Ex It illustrates a great disaster, but there is also hope here. Maybe not in this lifetime yet, but there is hope. Everybody dies, we just don’t know when I’m going to die, or when you’re going to die. Some deaths are inevitable, such as the ones that have been taken by the recent tsunami caused by a volcanic eruption. But others are avoidable. For instance, deaths caused by wars. This installation will still be important for a long time to come. Maybe people will associate it with the tsunami I mentioned, maybe with other natural disasters, maybe with the current state of the world, maybe with wars. Yoko doesn’t want to explicitly state and dictate what people should see in this installation, what kind of disaster it implies. As in all of her works, there is a lot of space for the viewer’s imagination.

How did you decide to exhibit this installation in the premises of a bank? The actually functioning bank and the banking operations happening in the same space as the installation create a strong additional field of associations and meanings for the piece.

This space was suggested by CAC director Kęstutis Kuizinas, although the initial idea was to place it elsewhere. It is usually exhibited in gallery spaces, but we have also presented it in a church and outside a cemetery. The bank space adds even more different meanings. I think this space is very suitable for the installation. Equally important is the beautiful architecture of the building. But at the same time, I believe that any space can be fitting to present this installation. And all spaces would bring their own meanings because all spaces are charged with different symbols. The installation will change a little bit soon when the trees start leafing out. And after the installation closes, it will continue living, as the trees spread across the city. We will plant them ourselves or invite people to plant them in their parks and gardens.

Dovilė Grigaliūnaitė