Bal MAKHSHOVES

Rosian Bagriansky

2019-09-17

Lara Lempertienė on Lea Goldberg

2020-09-29

Bal-MAKHSHOVES

The Butchers’ Synagogue

Transl. from Yiddish by Daniel Kennedy

If all the buildings now being renovated were able to speak it would be impossible to bear.

Every little ruin currently being fitted out with a new set of roof-tiles or a couple of new windows would bombard us with all manner of stories . . . tales dating back to the time Jews first began to spread out from the fish market as far as Poyarkov’s wall—stories of transgressed boundaries, stories of narrow windows peeking over into Reb Itsik Velvl’s property; stories of a dozen heirs who could not agree on how to divvy things up, quarrels passed down from parent to child, dozens more heirs joining the fray with each new generation; stories of the expulsion from Kaunas, when the houses became dark grass-widows; stories of the Germans who commandeered houses and melted down every last doorknob to make bullets; stories of one regime after another turning a blind eye to fine Kaunas furniture, tearing out the floorboards one by one; stories from the fires, when a Jewish woman ran through the streets, clutching a quilt to her bosom, searching for her sick mother who had not managed to save herself, reduced to a pile of bones, and so on and so on.

But these refurbished edifices are naturally silent, and even if you hammer a seven inch nail into them they remain as mute as a fish.

There are some ruins, however, that do occasionally find their voices, recounting wondrous tales in a manner only women and the elderly are sometimes prone to. These voices usually belong to those buildings equipt not with a sink, but with a ritual washstand for ablutions; buildings which, in place of beds, have only a narrow board on which a recluse has sat for twenty years of his young life; instead of mirrors there is a pulpit, where the readings are sometimes interrupted by the arrival at the door of a worried, disconsolate mother, where sometimes a young man lets his mind wander when he should be grasping the roots of the Torah.

Ruins like these do not stop speaking even when cats and dogs roam through their old crumbling furnaces, when rubbish from the neighbouring Jewish houses accumulates in mounds in these once sacred places. If you happen to stroll past the hollowed out skeletons of such buildings in the evening hours you may hear voices, speaking and reminiscing, often with insistence.

Now there are honourable people walking around Kaunas, with the faces of synagogue gabbais, with wide spade-shaped beards shot through with grey, with sober gaits and movements, with preoccupied faces—seeking out former owners, the children of those who once had a connection to these holy places of yore. They rattle their collection boxes, saving up to rebuild, brick by brick, a synagogue, a Butchers’ prayer house. They visit me too. Me, who has not set foot in a prayer house in many years, whose only memories of a place of worship go all the way back to childhood.

All of a sudden the Butchers’ Synagogue begins to tell me story after story. And just like that I pictured Leybe Pak who used help poor women recite the prayer before dying as they drew their last breaths, and I could suddenly hear the old mournful, stubborn voice of Avrom Kez who, every Friday evening of his life, would run around warning the shopkeepers to close up shop before the benediction of the candles. I caught a shining glimpse of the coppery-red beard of tall, broad Yerukhem the knife grinder who used to set down his whetstone and wheel by the synagogue, sit down and fervently leaf through the Zohar, the poor man struggling his whole life to grasp the barest meaning of the words. The twisted Jew from Vandžiogala—a figure right out of a Marc Chagall painting, who dealt in Leipzig lottery tickets, and had a year-round subscription to good old Kaunas mud—suddenly entered my thoughts. Also Reb Sholem the Recluse, that cheerful Hasidic scholar, who would dance magnificently during the few happy Jewish days, and who would implore old Dr. Faynberg to repent if he wanted to enjoy the Next Life as much as he had this one—he too came to mind when I was visited by the gabbais of the Butchers’ Synagogue. I suddenly saw the two rich men at the Eastern Wall, one calm and taciturn, the other a talkative man, full of spirit, a people-person—and I remembered the kind of politics that went on in the synagogue when Reb Yitskhok Elkhonen, the pride of Kaunas, deigned to visit once a year to consecrate the building by praying in the Butchers Synagogue. At that moment the highly fraught question was posed as to which side of the Holy Ark dividing the Eastern Wall would sit the great rabbinical authority, the pride of Lithuania: next to the taciturn dignitary, or next to the talkative one?

And among all these figures two faces stand out: jolly, chubby Shaye the Magid, and Yekusial the head-Shammas, who was tall and lanky and had a pitch-black beard like something out of a story book. Shaye spent every day on Butchers’ Street where the Butchers’ Synagogue stood. Even on Simchat Torah, when he would dance with a broom in his hand he never left the boundaries of that street. The street marked the limit of Jewishness. Beyond there were already church shops and a policeman patrolling the pavement.

All of the aforementioned figures arose in my memory when the gabbais from my father’s old synagogue paid me a visit. Seeing those already distant figures I thought: you can look at Jewish prayer houses from whichever perspective you wish but one thing is undeniable—they have always been safe havens for all kinds of wonderful characters, for men of duty, frightfully original, genuinely striking folksy characters. To this day our entire political and societal life has not created a fish pond to match these places, capable of nurturing such strong down-to-earth personalities. There were once the Cities of Refuge, for those who had unwittingly transgressed—in our epoch the prayer house is the modern City of Refuge for these wonderful specimens who emerge from the life of the genuine Jewish people. There you will find the archetype of the Jewish labourer more clearly articulated even than in those circles where people debate Marx without a Holy Ark or a pulpit—that is to say: without the wonderful thousand year culture of a highly spiritual and downtrodden people.

That is why the ruins of the Butchers’ Synagogue speak so louding to poets and the elderly alike.

April 1921

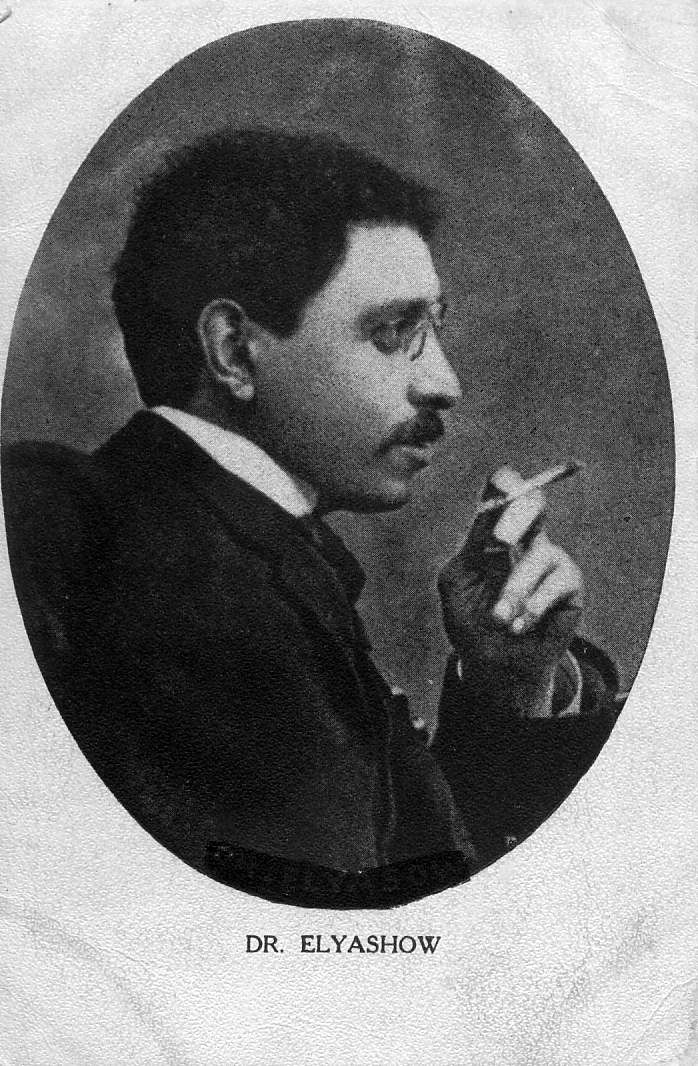

“Di Katsovishe Kloyz”. Bal-Makhshoves (dr. Is. Elyashev). Untern rod. Gezamlte shriftn. Band V. Berlin, Nyu-York: Bal-Makhshoves-komitet, Y. L. Perets-fareyn, p. 289–292.

Kaunasian Bal Makhshoves (1871–1924) – a famous Jewish literary critic and doctor. Real name – Israel Isidor Elyashev.

If all the buildings now being renovated were able to speak it would be impossible to bear.