Tebby Ramasike, who will perform at the Ninth Fort: “In ugliness there is beauty and in darkness there is light”

South African-born dancer and choreographer Tebby W. T. Ramasike has three decades of experience working on a professional stage. Ramasike doesn’t avoid drawing resources from painful historical events, which he combines with his personal experience and expresses in body language. On 24th of September, 2022, he will perform the performance “The Wreckage Of My Flesh” at Kaunas Ninth Fort Museum. In order to learn more about the performance, the dance in the context of traumatic experience, and the importance of remembering historical events, we invite you to read the interview with Tebby Ramasike.

The performance “The Wreckage Of My Flesh” is a part of the international project “ECCE HOMO: Those Who Stayed”, which is organised by Kaunas Ninth Fort Museum and Kaunas European Capital of Culture 2022.

On 24th of September, you will perform "The Wreckage Of My Flesh" at the Ninth Fort. First of all, I would like to ask you what impression and emotions did you have after visiting the Ninth Fort for the first time in 2021, during the preparation for the project?

That was quite an overwhelming experience. I saw pictures before that Bruce [visual artist Bruce Clarke] had shared with me, so I expected a different place. But when we were there, I just felt – Wow! At first, I didn’t know how to express it. I was so overwhelmed… I felt there was so much pain… There was a voice inside of me that was screaming out of pain, there was a voice screaming out of hope. It actually exceeded my expectations. I felt I was standing on a sacred ground. There was this intense and unique energy. It was not the structure of this place that actually caught my attention, but the surroundings, the environment, the trees around there... The trees became a representation of this symbolic nation of people that lost their lives there. There was the spirit that was living.

What was very interesting for me, is that I was not walking into a museum. I was not walking into an exhibition space. I was drawn into the living soul of humanity. Humanity that has been lost. I just connected with something there and creative ideas just flew immediately into my head. And I said, “I think I came to the right place. This is where I belong, this is what I wanna do.” My soul, my heart was pumping, and my spirit just wanted to live, wanted to grab, wanted to fly. It was so enriching for me.

Could you please shortly present your performance, which you will perform at the Ninth Fort?

I will go back to how the project started. In 2018, I was performing in a Butoh and Acousmatic Music festival in Paris. I happened to perform to Jacob’s composition. There was another Butoh dancer Denis, who was the original collaborator with me, but he unfortunately became very ill. He was performing to René’s composition. I was challenged by Jacob’s composition, which was short, complex and something that I’ve never dreamt of performing to. It was difficult, but during the performance everything just came together. I liked Denis’ performance and the composition by René. Then I said to the three of them that my idea is the four of us to be in the same space, we as dancers creating the dance, and you as composers composing at the same time. I proposed to them to collaborate, it was a small project for Amsterdam.

Then I started to develop ideas about the Holocaust and Apartheid. At the same time, I was writing a poem, and the title was “The Wreckage Of My Flesh.” This poem was inspired by seeing images of the Holocaust. I just put everything – the Holocaust images and the Apartheid images – together. At that time, I got very ill. I was hospitalised, I had 3 surgeries. I was in a hospital and all these images were coming back to me, and I felt like I was a part of that. My body was just disintegrating. I felt that my flesh was becoming wrecked, so I just said, “The Wreckage Of My Flesh.”

Next thing was – what do I do with this? What was the main focus in this project? Is it about the Holocaust? Is it about Apartheid? Or is it about me hospitalised and dying in my hospital bed? Being a Butoh practitioner, I’m always working a lot with the body. And I say – it was about the body.

When I saw my parents in South Africa after a long time, their bodies were deformed, changed. Then I started to think about the people in the extermination camp. When their bodies were put in these ovens, what happened? I started to think about people who were banned in South Africa. My very best friend from growing up – I saw him being tortured and burned, I saw his body… So, this was about the disintegrating body that is changing, that is being deformed.

Having experienced being in that hospital and fighting, affected me psychologically. It was a struggle. At the same time, I had to perform a piece. It was about dealing with the resistance to oppression, the resistance to the struggle. It was also about hope, about the fight against something, about resilience.

Thinking about these bodies as they were in the ovens or burning, I thought of the voice of their silent screams. I had this image of the body screaming. The body becoming the voice and screaming out. That voice became my inner self territory. For me, dance became my saviour, my healing notion. These voices in my head became like – “keep on dancing, keep on dancing and never stop to dance.” I had to dance to survive. I keep saying until today, if I didn’t dance, I probably would have kissed this life goodbye a long time ago. Dance has helped me to keep on going. Also, through dance, it helped me to resist. And never just stop and have that hope.

People ask if this piece itself is about the Holocaust. It’s not. And it’s not about Apartheid. Even though I’m drawing resources from this human history of horrific events that happened in the past (unfortunately, they are still happening now), it’s also about the social crisis that we, as human beings, are finding ourselves in. It’s a silent way of saying something with the body, bringing out that pain, bringing out that suffering, addressing something that many would not actually address, through dance being the voice of the people who have been silenced.

I decided in this piece to use the genre of Butoh, which carries the body’s resistance to gravity. For me, it’s a strong way of taking the body out of the comfort zone into an unknown territory. At the same time, it’s something about an inner freedom, which is experienced through Butoh or through the ritualistic dancing and even through electronic music, which also has its own way of resistance.

You have mentioned the Butoh genre. What thoughts and feelings do you have during the performance of Butoh dance? How does Butoh stand out from other genres?

It’s a transcendence into another world. I work a lot with spirituality, and I try to connect this with ritual dance and with my Butoh practice. For me, it’s always like a spiritual journey. I always have a feeling that I’m transcending from one life to the other. I’m transcending from the existence into the non-existence.

Butoh gives me this feeling of going into a deep subconscious world. I’m on a plain of that higher level of spirituality or maybe existence. But at the same time, I always have questions at the back of my head. Where are you going with this? Every question that I have raises a different feeling, a different thought. So, it’s never the same.

It’s still a growing thing inside of me. I cannot say I’m an excellent Butoh dancer or I’m a bad Butoh dancer. I’m a Butoh practitioner, I just practise. I developed my own concept of Afro-Butoh. I could say Butoh has actually enriched my dance career. I’m looking at dance and myself as a dancer from a different perspective, understanding my body, my thoughts.

How does Butoh genre stand out from the other genres? Well, the first thing, people are afraid of it. [laughing] When we talk about Butoh, they say, “Oh, is that one about ugly bodies and death?” It’s the way people respond to Butoh. People don’t want to deal with something that has to do with pain, suffering and death. Especially with death and darkness. I always say to people, in that ugliness there’s beauty, in that darkness there’s light.

Let us pause for a moment to consider beauty, light, and dance – what, in your opinion, is the dance in the context of tragedy and traumatic experiences? A tool to empathize with other people's experiences? A way of healing?...

It’s not an easy question to answer, but I will try. If I look at it from the general point of view, it’s not that very easy, but for myself personally, it’s actually easy to work with dance and express traumatic or tragic experiences, because I dealt a lot with that. Even though people always say that I’m very happy, my world is actually tragic or traumatic.

I take a lot of people’s tragic and traumatic experiences into me, I listen to their stories. Sometimes I do make their stories my story. I basically put myself into their situation. When I start to do that, then sometimes I can create something out of that. Through dance it’s easier for me to express this. I also find that through dance it helps to heal myself. I could be caring so much and everything could be happening to me, but once I start to put this into dance, I feel this healing notion. As people have said to me, I’m bringing light into the darkness of their lives and I’m healing them. That’s why I’m always looking at my work from that spiritual healing notion.

One should not say, “Oh, my piece is gonna be about traumatic experiences.” I think if I start to say that, my dancers will rush out of the door. And I think if I tell the public that, they are not gonna come and see the performance. [laughing] It’s something that you keep into the work. A traumatic experience is not something that you put on the table just like that. It’s inside of somebody. Everybody deals with trauma in a different way. Every traumatic experience is on a different level as well.

In some of my dances, actually, I do express a lot of my traumatic experiences, which scares me at times. Then the problem becomes, what is the audience feeling when I go through a traumatic stage? Dealing with that through dance also helps me to release something, it heals me, it cleanses me. It’s like a ritual for me. It becomes like a ceremonial journey. Dance for me, and I think for many people, is healing, therapeutic. It’s a shame that many people don’t see it that way. They only see it as a hobby, as just dancing. They don’t realise that when you dance, there is something inside of a person that is happening. Dance brings joy, life, light, dance heals many people.

Let us go back to your performance at the Ninth Fort. An international team is contributing to it. Could you please introduce your team members?

I’m just gonna make a short introduction about them. I will start with René. René Baptist Huysmans is from Amsterdam. He is a composer and sound artist. He specialises in collages of electronic sounds and field recordings.

Jacob Elkin is from New York in the USA. He is a multi-instrumentalist. He is teaching at the United Nations International School and he is a specialist in electronic microtonal music. Don’t ask me what that is… This is why his music is very complex. All these terms… It’s not the same electronic music that we know. [laughing]

Denis Sanglard was the original member of the team, but because of health problems, he couldn’t continue with the project. He’s a Butoh dancer and an actor. He’s still very much involved in the piece, but more like on the sideline, as a coach or just giving feedback.

And then we have Ellen Knops, who is from Amsterdam. She is our lighting designer, and she loves to improvise and play around with the location. She’s the person who goes to a location and sees what the energy of the location is and what it gives her to do with the lights. She worked on many of my productions. She’s a fantastic person to work with.

Then we have Anne Oomen. She’s from Noord-Brabant. She’s a Dutch fashion textile designer. She specialises in silk. She works a lot with dancers, with movement. She was also a dancer herself as well. She translates a fascination for dance into the smooth movement of silk. Her work is very interesting to see on the body of the dancer. That’s also why I chose her. For many years we wanted to work together, this is finally the first project. She gets her inspiration from abstract painters and modern artists.

And then we have Elizabeth Damour. She’s from Paris. She’s a French Butoh performer, psychotherapist. She enjoys sharing, transmitting and connecting with the continuous development process. She works with young people as well. Elizabeth actually first joined the project as my assistant, not as the dancer. Then eventually, when Denis couldn’t continue, the only solution was Elizabeth.

Now we have Zo Fan. She’s an external artist in the project. She’s actually Bruce’s assistant. She was suggested by Bruce to be our videographer. She’s from Singapore, but she lives in Paris. She’s a film director, photographer and videographer.

Many people contributed to the project as well. It’s not only us; there are other people who are involved from the outside.

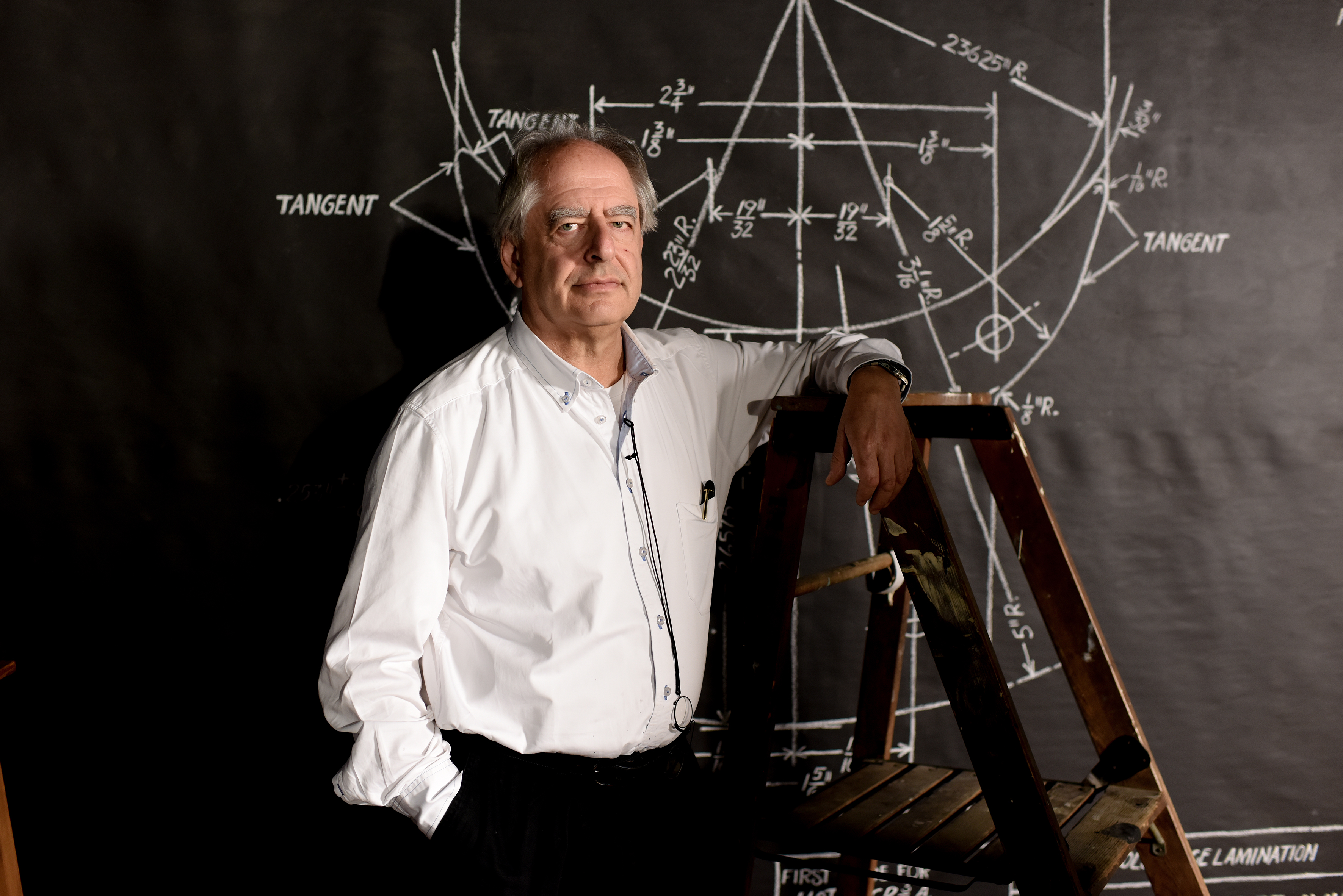

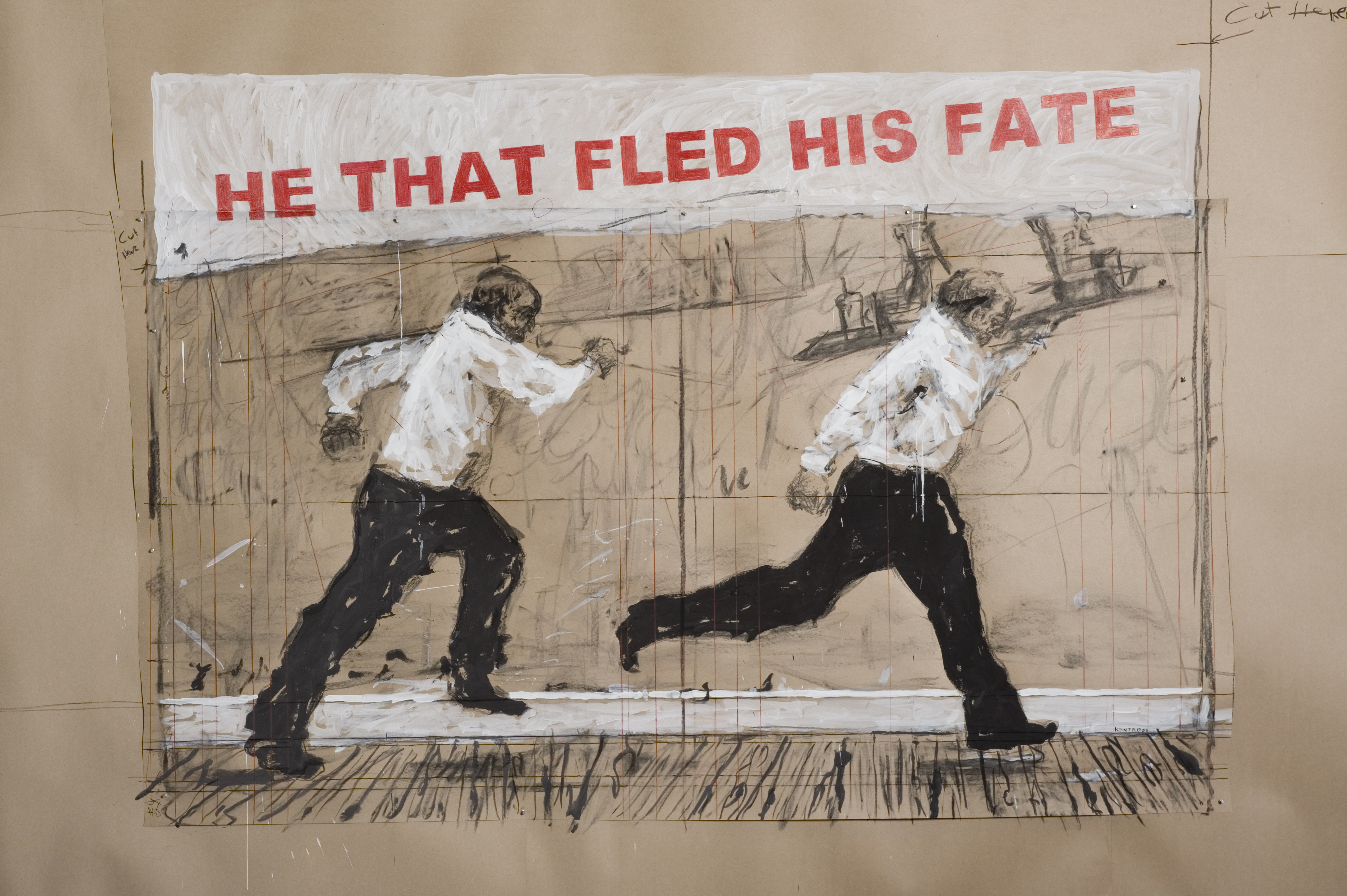

Your performance will be closely related to the exhibition by the artist Bruce Clarke exhibited at Kaunas Ninth Fort Museum – the dance will be performed in its background. What is the relation between the exhibition and the performance? How do they complement each other?

It’s interesting, because I didn’t know Bruce in the beginning. Frank [Frank Schroeder, the director of the National Museum of Resistance and Human Rights] knew my work and he knew Bruce, so he had invited Bruce to do the exhibition [in Luxembourg]. But I think when he saw Bruce’s work, then he saw me. The first time I saw Bruce’s sculptures, it was like: “Where did you find me?” [laughing] I also saw myself. I think it became like an instant connection.

What actually attracted me to Bruce was his background, which was like born in the UK, having a Jewish family, and [relations] with Lithuania, and the family in the Holocaust, and living in South Africa, being part of the Apartheid struggle. Then I saw his works and I was totally seduced. I wanted to know more about his works and I started to have ideas. What also grabbed me was his work in Rwanda with the genocide. I was just thinking, “These all are traumatic. These tragic situations that brought up a lot of trauma in people’s lives.” And I liked this because this was Tebby. [laughing] So, I thought, “I’m not going to have fear of actually trying to relate to his work. I’m just going to be an open book.”

In the past, I used to have artists that I would dance what they have painted or their sculptures. But now it’s different. We try to tell our stories in a different way and yet complement each other. What we also decided to devise, is this inter-dialogue between me and these sculptures, how I use them, because they have to be another performer.

This is something very interesting about the Ninth Fort Museum, it’s something that actually came to my mind: if we have these sculptures of Bruce and I’m relating to this installation and leaving the space, what happens? My idea is that you build up this relationship with these sculptures and you leave, and that relationship should still stay there even if my physical body is not there. It should stay within those sculptures because they’ve been part of the performance. It’s something that is possible because I always have this thing that an energy, that has been established, even when you leave the space should stay. I mean, when I went to the Ninth Fort Museum, even when I left, I could still breathe that energy.

What happens to me? This is another thing, the relationship between the installation and the dance. What happens to me as I dance with those sculptures, as I connect to those sculptures? What happens to me afterwards when I leave as a dancer? Do you just leave and then forget about them? No. I could choose to do that, but I don’t want to do that, because they are alive. It’s a major piece of artwork, so very important. I really have found something powerful in Bruce’s work that can actually enrich the dance.

Finally, the last question – why, in your opinion, it is important and necessary for today's person to remember traumatic experiences such as the Holocaust?

What happened in the past and what happened during the Holocaust is building our future. It’s part of our history. Whether you are Jewish, whether you are African, whether you are European... It’s part of us, it’s not only part of the Jewish community. It’s part of the world we live in. And, unfortunately, what happened during the Holocaust is actually coming back – it’s happening now. Even on a different scale, even in a different way… But I see it growing. I see it coming back in France: the nationalists are coming back. Then there’s Putin. He wants to be the master race, like Russia has to be the master race again as Hitler wanted Nazi Germany to be the master race.

Of course, people don’t want to deal with trauma, they want to distance themselves from the Holocaust. It was not a tragic story, it was really traumatic, something that kills the spirit of humanity. To be able to keep that as a memory is to believe, to understand it and to put it in that place of importance. It’s not just an event that happened and you leave it behind. It’s an important event in our historical lives as human beings. And it's really necessary for the generation now, our generation in the past, the generation in the future, to understand it, to remember it, to know that it happened. Because it will happen. We have already been saying that history repeats itself.

I just hope that the world will open up, believe, and finally say, “We understand,” and stop being in denial. The Holocaust did happen, traumatic experiences that people have gone through have happened and we cannot deny that. It’s a shame, because that denial is actually bringing up a lot of violence, which is scary.

The interview was prepared by Henrika Kryževičienė

The performance “The Wreckage Of My Flesh” by Tebby W. T. Ramasike will be performed at Kaunas Ninth Fort Museum on 24th of September, 2022. More information about the event can be found at Kaunas Ninth Fort Museum website: www.9fortomuziejus.lt/?lang=en

The project is a part of Kaunas European Capital of Culture 2022 programme.

The project is implemented by Kaunas Ninth Fort Museum and Kaunas 2022

Information partners: LRT, “Kauno diena”, KB “Katos grupė” | ACM

Partners: National Museum of Resistance and Human Rights (Luxembourg), Esch 2022

Kaunas “Summer Stage”: bold statements by the Ukrainian group FO SHO

Kaunas – European Capital of Culture 2022 is organising an empowering and spirit-lifting party for Ukraine day on June 11th. On that day, the “Summer stage” will be filled with powerful music and deep connection provided by the Ukrainian music bands TONKA and FO SHO. Members of FO SHO are vivid truth seekers. Their hip-hop and RnB style mixes with political and social topics. For the upcoming event, we interviewed the unique Ukrainian trio.

How did you come up with the idea of creating a band?

We are real sisters. We were always singing together and harmonising all our life. We knew that we had a huge age difference. I was older, and we will never be able to form a band. At some point, we took a selfie picture and understood that we looked like a band. I was writing a lot of songs, and I showed her a track called “xtra”, and she fell in love with it. And I said, “let’s do the song together”. And she said, “really?”. So, that’s how our first track came out.

Your songs are very empowering and energetic. Where does that power come from? What is the main message you are sending through the music?

It’s the fact that every person has their unique side, craft, you name it. And that makes every person stand out. And as soon as you find your craft, you are extra. And by the time you are born, and you have a life, you’re son or daughter or parent, you are a human being - you are extra. And everybody has their own background and their own shape, and everything makes us stand out somehow. So, if you think that you have some imperfections, it actually becomes perfect and makes you interesting and extra. We are trying to empower and give people the energy and remind that they are unique and beautiful. Each and every one of us. We also grew up in unique surroundings ,– we were black girls in a Slavic world, and we had our own struggles. In every country, people can find their own stories and be inspired by them if they look from the other side. Not from the negative but from the positive side.

Few days ago you were performing in Forbes Under 30 Summit. You were rapping in the Ukrainian language. Some would say it’s impossible. How did you come up with rapping in your language? Is it new or common in Ukraine?

It’s a new way. It’s a new way because hip-hop hasn’t been popular in Ukraine at all. Ukraine is a Slavic country, and here, in Russia, in Belarus, in other countries like that, they are more into balladic music. So now hip-hop has become interesting nowadays. It’s a challenge. It’s something new. Some say it’s impossible, but we can make it possible. We accepted the challenge. We love our language, and we are exploring it. We are now writing in the Ukrainian language because it is vital to support the culture, especially in these hard times.

Your band performs in international concerts. Isn’t the Ukrainian language a barrier to understanding what you are singing about?

First of all, music is a universal language. Sometimes we like songs without understanding the language, but you can appreciate the beauty of the music. Secondly, the Ukrainian language is a challenge. And not everybody will understand it, but everybody will be able to see the beauty and how this language tastes. It’s a new flavour, and it’s awesome. In order to make the message more digestible, we wrote our first singles in English mostly, because we had something important to say and we wanted the world to understand it. We also wrote a couple of songs in Ukrainian language. During the war we released a song called “U CRY NOW” and it’s both English and Ukrainian.

Regarding the situation in Ukraine, do you think culture, for example, music, can be the right tool to fight in this war?

Yes, absolutely. Culturally music is a tool to say our truth and speak the truth. Also, we are using our pages on Instagram and Facebook to spread the truth about Ukrainians. And you know, we believe that every craft or business can be used to create peace between nations.

How does your band work? Do you write your songs and music yourselves?

In the beginning, I (Betty) used to write the songs that we recorded. And now Siona is in the process and writing together with me. We are our own producers. We understand what we want. We work with arrangers but we usually lead in the production process. Siona is a professional piano player, Miriyam is a professional violin player, we use these crafts in our music creating process too. We all are working for the same purpose.

What is your purpose as a band?

Our segment is hip hop and r&b. Hip-hop was always about the meaning, the statement you want to talk about. So, we are always about the meaning. If you check our song “BLCK SQR” - we are exposing the truth about Ukrainian artist Kazimir Malevich that Russian propaganda says that he’s a Russian artist. Meanwhile, he’s a Polish-Ukrainian artist born in Kyiv. We also talk about the fact it is a very weird world we live in. We have a lot of money for the covid, for war, for nuclear power, for bombs, but would we have enough money for those who die from hunger? Like, really, in Africa, Asia, many places. We have a lot of good things that we want to talk about. Political stuff. We are optimistic, but we are also about the truth and exposing the meaning that would help our society and earth become better.

Some say: don’t mix politics and culture or politics and sport. You are a perfect example that you must do it. But is it easy/difficult for you to reach that goal? Can music be taken seriously in this kind of topic?

Absolutely. During the war, musicians come to soldiers, and they sing and lift the spirit. Music has a huge influence on everyone. Whether you like it or not, it can switch your mood: make you sad or happy. We think that it’s a big thing and it has an impact on emotions. Sometimes people would like just to have fun: listen to music and dance not thinking about serious matters and that is also okay, but we also should not forget that music is a tool for a good change and that through music we can trigger people's mind to think about some useful topics. We think that right now, music has become so much about meaningless stuff, we want a change, and the change starts with us. There are people creating music with a meaning like Kendrick Lamar or Tyler The Creator, but they are few, so we are part of this minority in music field, that tries to talk the truth and make people consider other things and trigger their minds to think about some meaningful stuff. But we can also have fun. We are not always serious; we know how to have fun. So, we are creating balance.

You are coming to Kaunas “Summer stage” to perform for the Ukraine day we are going to celebrate in Lithuania. How do you celebrate it in Ukraine? Maybe you can share some insides for us?

Cultural food, like “Borscht”, “Palianytsia”. For example, whenever you meet someone for the first time, for the welcoming, we bring big bread that’s called “Palianytsia” and we bring salt, that’s how we welcome our guests. There's also salo, as jewish we don’t eat it because it's a pork meal but Ukrainians eat it. Of course, we sing Ukrainian songs, and we will teach you to sing them. We wear traditional Ukrainian clothes - Vyshyvanka. We also make a crown from different wildflowers like dandelions and cornflowers. Their colours represent the Ukrainian flag.

What greetings to Kaunas do you have?

We are super grateful for the support. It means a lot. You know, it’s like a brotherhood. Because first of all, we are all humans. We get a life in this world and become citizens of a country. We are all kids, and we are all human beings. And thanks to you for standing behind the truth and love. It’s a big thing, and it’s a blessing. We can’t wait to meet you.

Slava Ukraini!

Gerojam Slava!

Partner of the project: “Švyturys Non-Alcoholic”. Friends of the project - Ukrainian Institute.

For the complete Kaunas 2022 programme, please visit www.kaunas2022.eu or the mobile app.

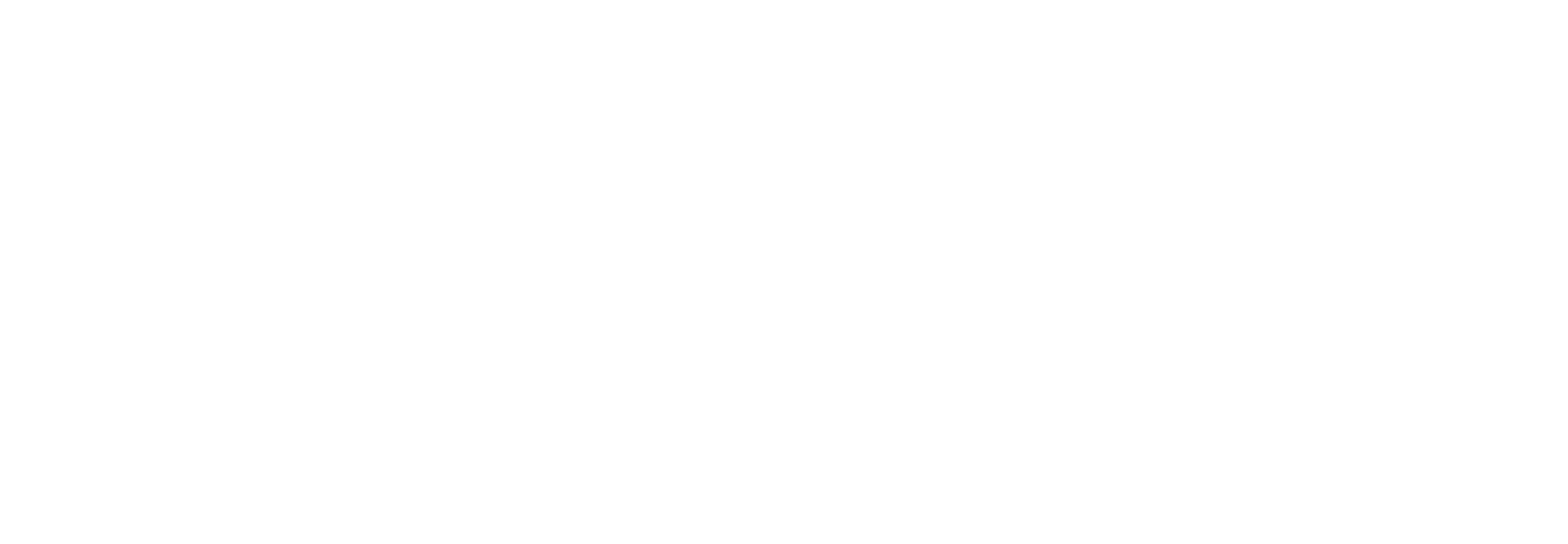

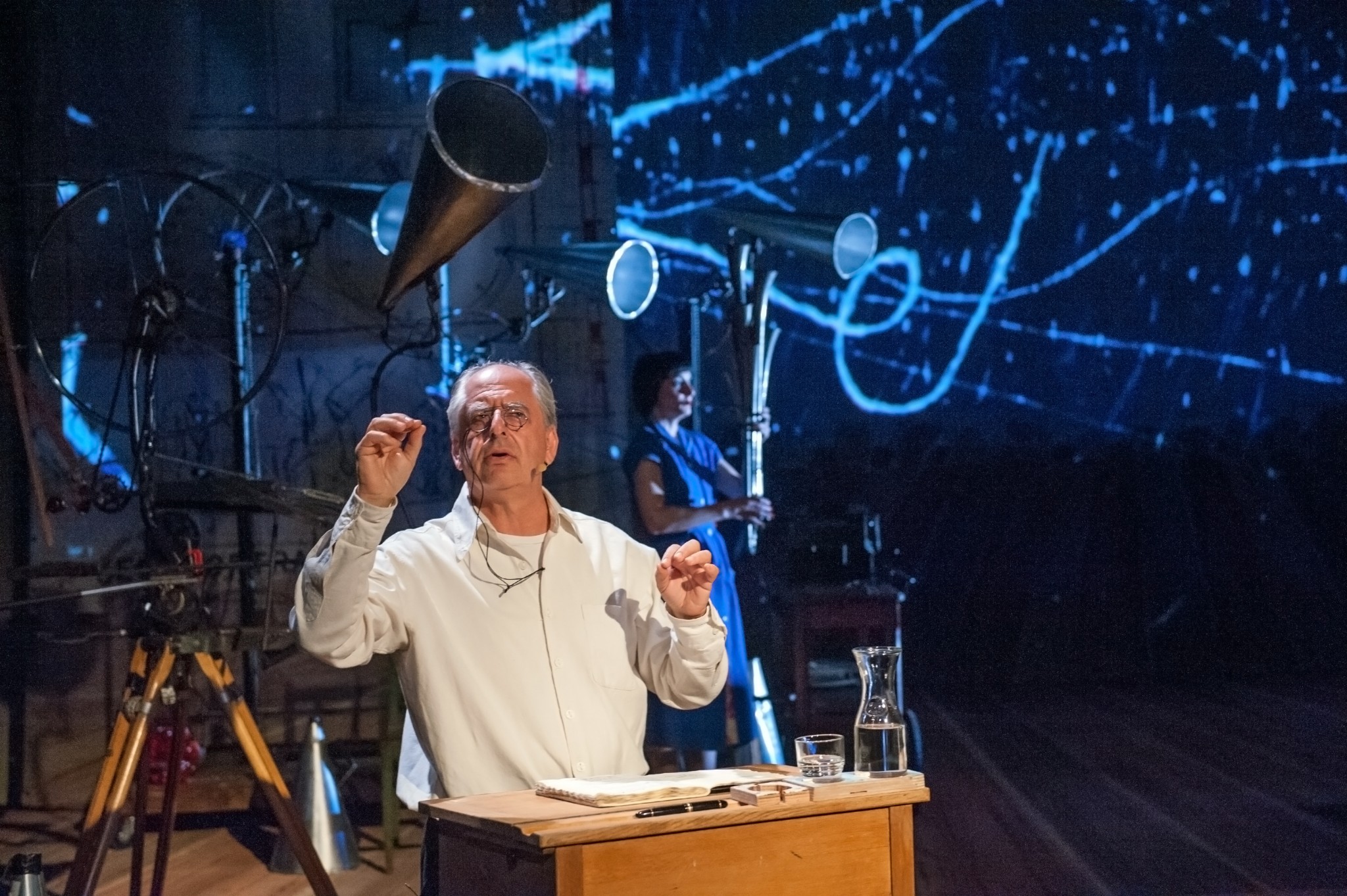

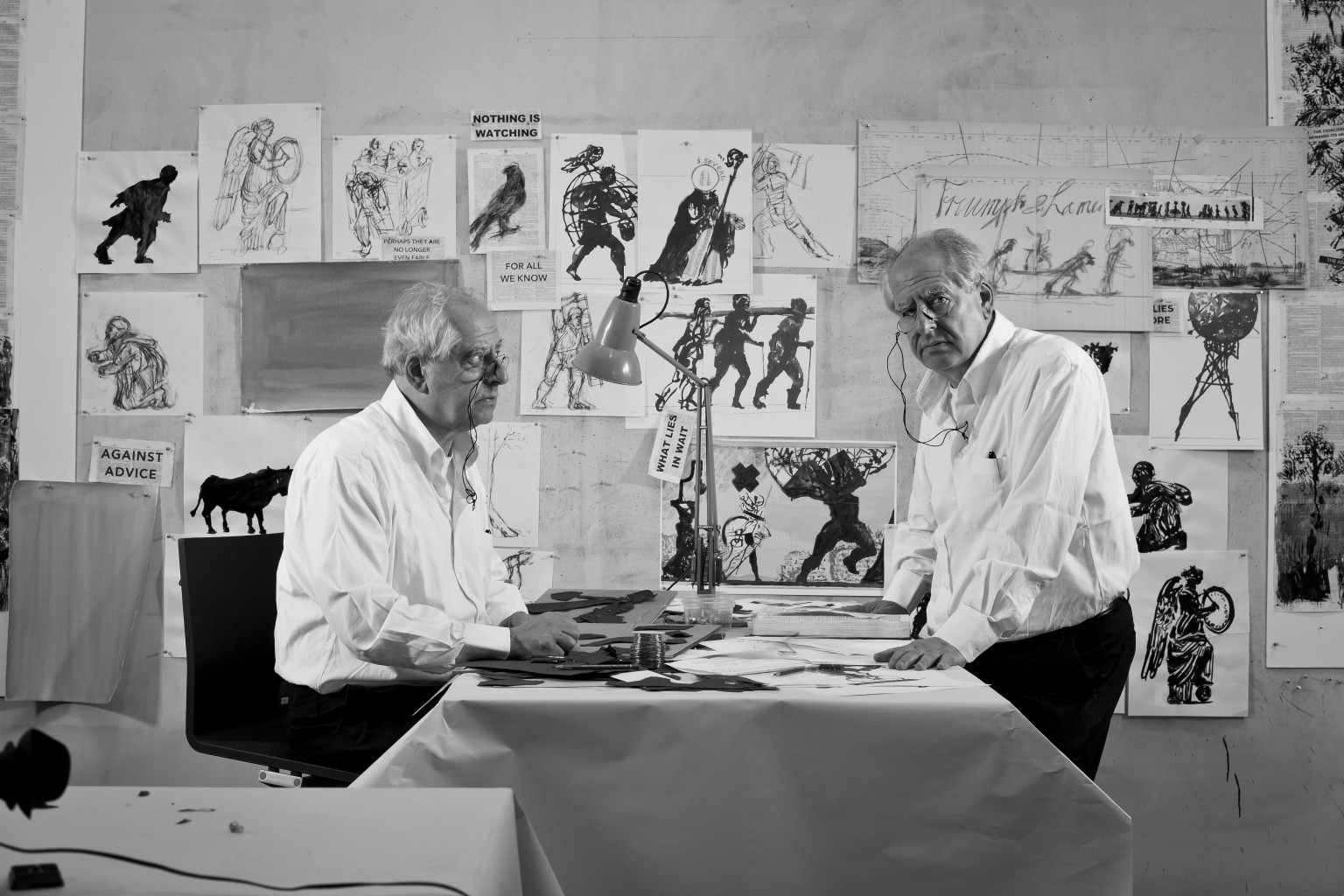

William Kentridge: Breaking the Forms of Constructed Ignorances

William Kentridge's grand exhibition (curator Virginija Vitkienė) That Which We Do Not Remember, which will take place at the National M. K. Čiurlionis Art Museum, should be noted as one of the most important events in next year's “Kaunas – European Capital of Culture 2022” program. Born in South Africa, in Johannesburg, in 1955, the artist with Lithuanian roots has been known and honored in the arts for many decades, and his works have visited the world's most important galleries and become part of large collections. Kentridge is an intellectual who provokes emotion and reflection. His sources of inspiration range from science to literature, and his artistic means range from charcoal drawings, paintings, textiles, animated films to opera productions. This reflects the author’s own educational spectrum and wide field of interest.

- You studied a lot yourself and you certainly had great teachers. Are you a teacher yourself?

- My wife likes to tell the story about Jewish husbands: they never leave you but when they turn fifty, they become rabbis. So sometimes I think I have become a 66-year-old rabbi. And in the context of The Centre for the Less Good Idea, a lot of what I do is in a role of teaching.

For years when I was asked to teach, I thought, well, I’m still learning, I've got nothing to teach. Now I feel I’m still learning, but I do have something to teach. And more than that, often I learn from working with the younger artists.

There’s been enough experience in the studio; sometimes now I am able to respond to the misery of the anxieties that younger artists have, and which I had when I was much younger. Not that there aren’t anxieties now, but they are different anxieties, they’re not those of a young artist.

- What gives you the courage to create?

- The activity of continuing with work day after day, whether you’re a writer or a painter, is hard when you’re starting. I think that requires more courage than it does to keep going when you’ve got a trajectory and a momentum, and an experience of projects having worked out in the past.

When you’re starting out, every new piece is vital. If one drawing or one painting seems to disintegrate and be not worth it: is this telling me the truth about who I am? I’m doomed for things to fail! So, to get past that is a kind of artistic courage. It also takes a mixture of obstinacy, stubbornness, thick-skinnedness to not mind the responses of people to one’s work if they don’t like it. This is never something that I’ve been able to do.

I think to be an artist is so much about a psychic lack, a gap. This gap is feeling that in yourself you’re not enough. You have to leave this trail of objects and things behind you for other people to see, so that you can see yourself, looking at these objects. It’s not about courage, it’s about inadequacy.

- What connection, if any, do you see between originality and authenticity?

- Authenticity as a starting point doesn’t interest me. I’m interested in what emerges through the process. I’m more interested in stupidity, or another way of saying that: giving the whim, giving a quick idea, the benefit of the doubt and seeing where that leads us.

The vast majority of the projects I’ve done, and the discoveries which have been interesting to myself or to other people, have inauthentic origins. You start from thinking of one thing and then you’re following one idea, and then something else emerges. It’s not that a clear thought and a clear line of investigation lead to an answer to a question you’ve asked yourself.

- In our works one can notice a lot of negativity, reversing, negation. Is this your artistic tool? What does this mean for you?

- I’m interested in the negative in the photographic, metaphoric sense. The negative is what is recorded on that piece of film from which we make a second negative, which is the positive print.

You film the ants on a sheet of white paper moving around in their different formations and then invert: the white paper becomes the night sky and the black ants become spots of light in the night sky. You’ve made a herd of moving stars and planets.

That’s the practical sense of the negative, which is not the void, but it shows the explanatory power of darkness – rather than assuming, from Plato onwards, that everything has to do with light as an explanation, that one has to bring light to darkness to understand. Sometimes one needs that strange mixture of darkness and light for things to make sense.

A black hole in space as a place of massive gravity that will absorb all light and anything that it swallows. That finality. Of course, in understanding physics I am trying to make sense of our own black hole, a six-foot grave that we’re heading into, that void. If you can’t bear the thought of the finality of that void, you need to believe that something can still emanate from that darkness, in which case one believes in a soul.

- Quite often you involve entropy in your work. What is it?

- The artist’s job is to resist entropy. If you throw a vase up, it shatters on the ground. If you pick up all the shards and throw them back into the air, it’s very unlikely that they’re going to reform exactly as the intact vase was before it was broken. It’s that statistical improbability, which is the basis of entropy, of something that is ordered breaking down into a state of disorder. The artist’s job is to take those fragments, the shards of the vessel, those torn up pieces of paper, and reconstruct something new, a new image. The form is of collage, but it’s a different way of saying that we construct our understanding from fragments that we pick up all around us and inside us. That battle against entropy – and the fact that in the studio this is a battle that we win every day – makes entropy an important and good category to work with.

- What is your relationship with tradition?

- I am interested in mistranslation, in imagined context, rather than deeply understood context. I’m skeptical of an art of identity and the politics of identity, but rather interested in the politics of bastardy, of hybridization, of resisting tradition and believing also that most traditions are invented and constructed. Certainly, in the colonial world, the work that was done by the colonial administrations was to invent the tribes, the cities, the clans, the tartans of Scotland, to understand those as constructions rather than as things to be discovered.

We have to be aware of tradition, because even if we deny it, our eyes and our brains are constructed through all the things we’ve heard, seen and been told. Our eye sees differently to the way anyone’s eye has seen in the centuries before us.

- Could art be called the best tool for creating narratives of history?

- We have to understand different forms of constructed ignorances in which things are deliberately hidden from us, histories are hidden from us, archives closed, shameful facts burned. I think one of the things that I’m aware of now is needing to give more attention to the periphery, to the things which one puts in the side cabinet. To take them out again, look at them again.

Because of art’s way of working with fragments, of constructing meaning through collage, is that we can construct other narratives, and narratives of history as well, by putting together different fragments. So, what is a natural process in the studio – taking a fragment from one drawing, a detail from a photograph, constructing an image from these different fragments – is also a model of how we can think of history.

- Your upcoming exhibition is of impressive scope and will be given special attention. You have not visited Lithuania yourself yet. What is your personal relationship with our country?

- I've always thought of myself as being of that part of South African Jewry, the Litvak – people who came from Lithuania (which is where most South African Jews come from). But I’ve never been to Lithuania.

My grandfather in his autobiography only gives one sentence to the place where he spent the first several years of his life. He simply says: I was born in Lithuania, from which many South African Jews come, I left Lithuania and went to England.

I have no sense of Shtetl life, of my ancestors’ life in Lithuania. I have no wish for restitution, certainly not of retribution, of thinking that I’m owed anything by Lithuania.

Eleven years ago, my daughter visited Lithuania and found almost no acknowledgement of what had happened there. I’m interested to come to Lithuania to see how it feels and whether my imagined country and its history corresponds to what I find when I am there.

Kaunas and the surrounding Kaunas district are ready to become one big European stage next year, offering over 1000 events. More than 40 festivals, 60 exhibitions, 250 performing arts events (of which more than 50 are premieres), and over 250 concerts are planned to take place in 2022. All this is delivered by Kaunas 2022’s team of 500 people, alongside 80 local and 150 foreign partners. 140 cities in Lithuania and the world, 2,000 artists, 80 communities, and 1,000 great volunteers. The Official Opening ceremony 22th, January, 2022.

Full programme: www.kaunas2022.eu

Interviewed by Sandra Bernotaitė

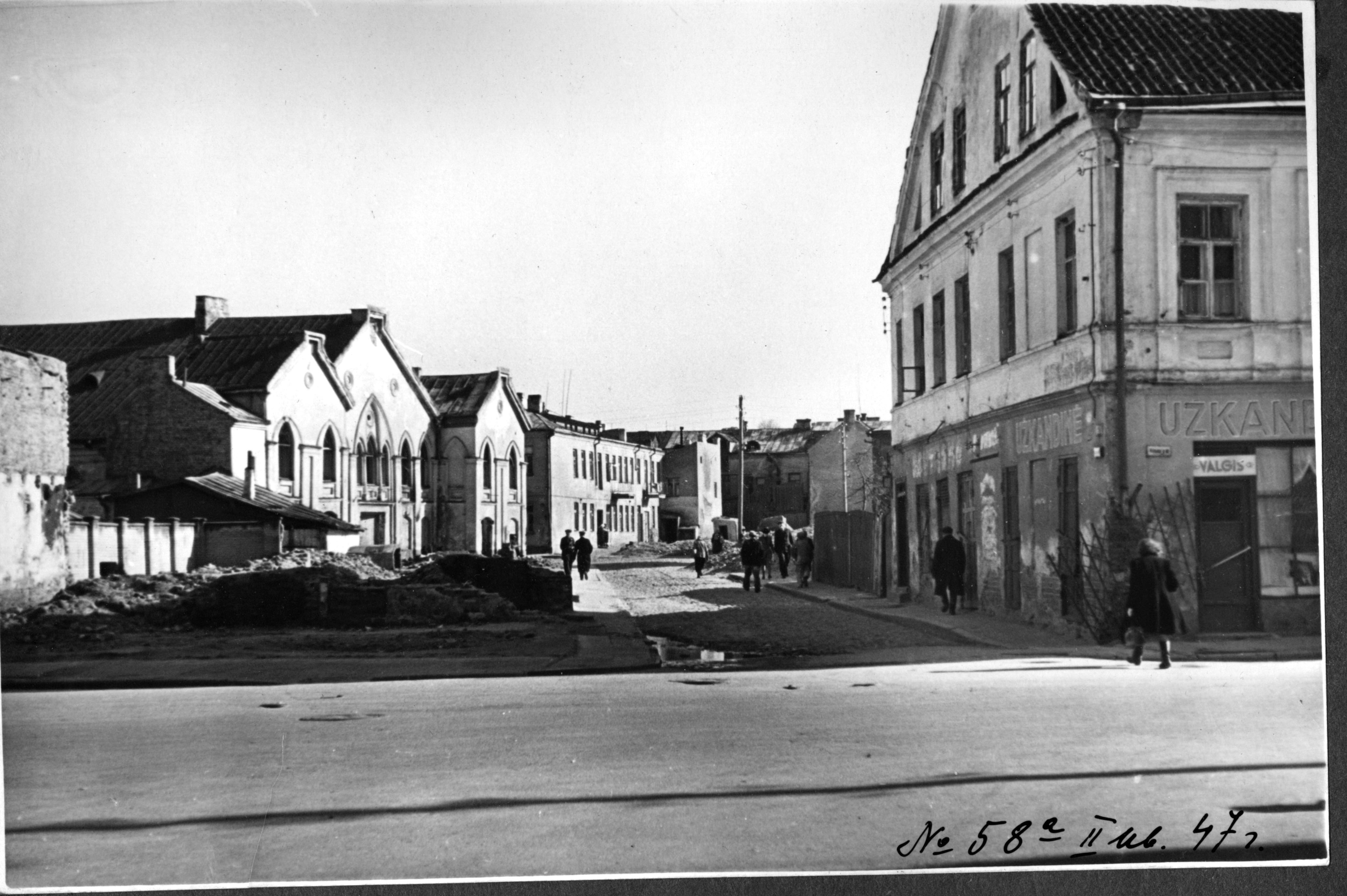

Daiva Citvarienė on “The Jews of Kaunas”: "Facts, dates and names are not enough to tell the story well"

To awaken the multicultural memory of Kaunas city and towns in its district and remind of its rich history is one of the most ambitious goals of the project Kaunas – European Capital of Culture 2022. To achieve that, the program Memory Office was launched together with the project. Just in time for the grand opening of Kaunas 2022, the team behind the Memory Office published a book called “The Jews of Kaunas”. Dr Daiva Citvarienė, the curator of the program, reveals the reasons for the book and her personal relationship with Jewish Kaunas.

- “The Jews of Kaunas” could take the shape of a film or any other storytelling form. Why a book?

- Of course, a film of such kind could be made. I want to stress that the Memory Office, part of the Kaunas 2022 project, has already presented a handful of initiatives that highlight the Jewish memory of Kaunas, including a series of murals reminding us of the Jewish citizens that once lived in our city. I believe the book is one of the most important projects of such a kind. We started working on its idea right after Kaunas secured the title of the European Capital of Culture. Firstly, we wanted to fulfil the gap in the city’s history. Secondly, we found it essential to create a sustainable product that would not end after 2022. In this sense, a book is much more durable than an exhibition or a stage performance. It is our tribute to the people who lived here and helped build the city, to those that projected their future in Kaunas, and whose lives were so brutally terminated.

- The articles in the book are based on numerous sources and illustrated with historical documents, photographs, many of which haven’t been publicised before, even advertisements. Which findings that helped shape the book were the most surprising and touching?

- I can’t speak on behalf of other authors, primarily professional historians – they probably have a different relationship with iconographic material. I’m not a historian; therefore, I do not really care if a photograph was already published and how rare it is. The amount of history in the picture is much more vital for me and its capability of telling a regular reader more about a specific time, person, or event.

What really made me happy was seeing a picture of the pergola the Kaunas-born Hebrew novelist Abraham Mapu wrote in. I had read about the pergola numerous times, and this photograph helped me better imagine the stories I had found and the city in those times.

Another discovery was a collection of the burned-down Kaunas Ghetto. These were some of the most shocking images of Kaunas I had ever seen.

No less important than illustrations are the memories and testimonies of people that lived or visited Kaunas. These stories also help illustrate history. I am happy we could include quite a few memories about Kaunas at the end of the 19th–the beginning of the 20th centuries, found in English-language sources. These enriched the picture of the city we tried to create with the book. Another significant source was the stories we wrote down when talking to current-day Kaunasians, including Fruma Kučinskienė, Julijana Zarchi, Bella Shirin and others.

- The book covers some five hundred years, yet it’s just 200 pages. How did you concentrate the narrative – there must be something left for future publications, right?

- I find it essential to stress that we did not publish a book for the academic society but rather for the curious readers interested in history. It is by no means an encyclopedia. I see it as an introduction to the world of the city’s past, a world not much explored yet. We included some of the most important names and their contribution to education, culture, medicine, industry, business and other fields of life, as well as the painful pages of history. I hope the publication will inspire future research.

Regarding the form of the storytelling, it was essential for us not to make this a list of names and facts. In terms of building a relationship with history, I find what museums do very interesting. For example, in POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, the narrative is based on quotes, memories and testimonies. We use similar principles in the book.

I am positive that facts, dates and names are not enough to tell the story well. To genuinely understand how people lived 50 or 150 years ago, we need to comprehend how they thought, felt, and saw the world. That is why we have included numerous quotes and memories from historical sources. These inserts are witnesses to time, adding life, breath and colour to the big picture.

- Did you encounter many contradictions in various sources? Is it easy to pick the most accurate truth when many event witnesses are not alive anymore?

- The research of the history of Kaunas Jews is still quite fragmented. We compiled the book together with historian Arvydas Pakštalis and aimed to collect what’s already done in the field, connect the stories, and fill some gaps. Arvydas is a keen visitor of archives, and he managed to correct some of the statements that have been floating around for some time now. On the other hand, I am sure that new facts and discoveries will appear after the book is out, and some more corrections might need to be done. I think it’s a natural process as the history of Jews in Kaunas is just beginning to be written.

- In recent years, we lost quite a few bright people necessary for the context and content of the book, namely Leonidas Donskis and Irena Veisaitė. Do you feel you didn’t have the chance to interview some personalities?

- Sadly, we dedicated the last pages of the book to those that left us too early, both Leonidas and Irena. It’s a pity we didn’t discuss the book with Irena when we still had the chance. And, when working on the text about Leonidas, we realised how little we know about the history of his family. Still, we found it extremely important to include stories about them and other contemporary Kaunasians and to stress that the Jewish history in Kaunas is still alive.

- The author collective is impressive. What was the book writing process like?

- Arvydas and I first collected what was already out there. The hard part of the job was connecting the fragments into a narrative; this is where Arvydas stepped in and filled the gaps. My task was to represent the reader and raise questions answers to which might seem obvious for a historian yet not always clear for an average citizen. I found it meaningful also to present traditions, culture and even the language – we decided to include a glossary.

- If someone decides to dig deeper into a period, a family or an event described in the book, which choice would make the Memory Office the happiest?

- As I’ve mentioned, these are only the first steps of the research of Kaunas Jews. The book could have been three times thicker! I hope some of the names we could not include will be remembered and researched by other authors. We’ll appreciate every initiative to revive the history.

- What were the first reactions to the book?

- The Kaunas Jewish Community knew about the process from the beginning, and I believe they were looking forward to reading the book. For us, it’s not just a tribute to people who lived there, but also a gift to the members of the community that became our close friends. For many of them, it’s a meaningful sign showing that their history and community drama are not forgotten.

- Can the book cause pain?

- It is painful for everyone that understands the size of the tragedy that happened in Europe and our city during WW2. Looking at the prewar photographs and understanding what kind of faith awaits the smiling people in them simply brings tears. One understands how much we lost by telling the beautiful stories of people who contributed significantly to building Kaunas. What’s hard to comprehend is how it could happen.

- Along with documents and photographs, the book is illustrated by original drawings by Darius Petreikis, who also created the Beast of Kaunas. How do the pictures enhance the texts?

- We did not aim for a traditional book full of facts and documents. We wanted it to cause curiosity. History can be fascinating, and it can be presented playfully. We’re speaking about a period of several hundred years about the community’s culture, traditions, and customs. We wanted to tell that story lightly, with a pinch of humour. After all, Jewish history is not just about the Holocaust. It’s so much more, it’s centuries of culture, traditions, customs, and it was important for us to remind that.

- Will the English version of the book become a meaningful souvenir from Kaunas, the European Capital of Culture?

- Indeed, the audience of the book includes Litvaks of the world and everyone else interested in the history of our region – this is why we prepared the English version, too. On October 29–30, the World Litvak Forum will take place in Kaunas; the Memory Office will invite everyone to more than 20 events dedicated to Jewish memory, including exhibitions, concerts and performances. I must also mention That Which We Do Not Remember, an exhibition by William Kentridge, one of the most famous Litvak artists, that will be displayed through 2022. Our book will be a meaningful bonus to the extensive programme and, yes, a meaningful souvenir.

- Daiva, please share some of the places in Jewish Kaunas that are the most important for you and still preserve its aura.

- I discovered the Jewish Kaunas some five years ago when working on an audiovisual route called The Spirit’s Guide to the old City. Looking for interesting objects made me stop in front of buildings I used to pass by every day and try seeing what’s not always apparent from the first glance.

I believe the Jewish Kaunas is still something hidden. Many signs of history have already disappeared or become unnoticeable. For this reason, the Memory Office initiated the creation of new murals inspired by old photographs and representing forgotten pages of our city’s history.

Speaking of the aura, one of such buildings for me is the current Kaunas Musical School No. 1 on J. Gruodžio St. In 1905, Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan Spektor established an orphanage in this building. Amazingly, you can still see the traces of old writings on the facade. Also, my son learned how to play the piano there, which I find pretty symbolic.

Another location essential for me to is my birthplace, the former Jewish hospital on A. Jakšto St. I am looking forward to seeing it alive again. Last but not least is the Kaunas Choral Synagogue, one of the most beautiful examples of Jewish sacral architecture, still waiting for its new golden era.

Places no longer identified as Jewish or not remembered as such are also very important. Among those are the J. Naujalis Music School (former Jewish Realgymnasium), VMU Law Faculty (Former ORT School), the former house of doctor Elchanan Elkes on Kęstučio St. or the New synagogue on Birštono St. which today is a car repair shop. I could also elaborate on the Old Town and Laisvės alėja, full of former bookstores, shops, barbershops, cinemas and restaurants established by Jewish businessmen. We must remember and remind this page of the history of our city.

Kaunas and the surrounding Kaunas district are ready to become one big European stage next year, offering over 1000 events. More than 40 festivals, 60 exhibitions, 250 performing arts events (of which more than 50 are premieres), and over 250 concerts are planned to take place in 2022. All this is delivered by Kaunas 2022’s team of 500 people, alongside 80 local and 150 foreign partners. 140 cities in Lithuania and the world, 2,000 artists, 80 communities, and 1,000 great volunteers.

Full programme

Chris Baldwin: Breaking down a boundary and stereotype means to actively help in the process of making new meanings, more useful cultural works

Chris Baldwin is a director, writer, curator… But he is so much more than these definitions. For many years now he has worked across the continent and has added to the success of a handful of European Capitals of Culture. This experience, together with his natural openness to the world and its cultures, make Chris a true European. No wonder the artist was invited to co-create the unique symphony “Šaipėrantas” (composed by Antanas Jasenka, conducted by Modestas Pitrėnas) for the grand opening of Kaunas 2022 on January 22 at 7:30 pm. The director got to know Kaunas intimately during this process – he also agreed to tell us more about his understanding of Europe and Europeanness.

Chris Baldwin is a director, writer, curator… But he is so much more than these definitions. For many years now he has worked across the continent and has added to the success of a handful of European Capitals of Culture. This experience, together with his natural openness to the world and its cultures, make Chris a true European. No wonder the artist was invited to co-create the unique symphony “Šaipėrantas” (composed by Antanas Jasenka, conducted by Modestas Pitrėnas) for the grand opening of Kaunas 2022 on January 22 at 7:30 pm. The director got to know Kaunas intimately during this process – he also agreed to tell us more about his understanding of Europe and Europeanness.

Below is an interview with director Chris Baldwin.

- Being British, how did you start working in countries that are considered post-soviet or post-authoritarian? Was it an adventurous decision?

- Ahh. Being British! I don’t really know what that means. I was born in Oxford in the early 1960’s. I was the younger one of post-war siblings. So we grew up with quite a strong sense of what being British was supposed to mean. We had, after all, with the Americans helping out, won the war against Germany. So being British was about fairness, democracy and standing up against the bullies. It was only as I grew up, and had some great teachers, and watched some fantastic BBC, that I began to realise that all this was a rather comforting myth, and that reality and history was rather more complicated. The problem with believing such myths is that it leaves you open, it leaves people open, to being vulnerable to the next myth which comes along. In these times of Brexit, the Britain I knew has been re-configured beyond recognition to me at least.

And then you also use the words ‘post-authoritarian’. A ‘post-authoritarian’ country is an interesting term - and I have used it in my own writing. It suggests that authoritarianism is something that has been left in the past. But recent events in various countries suggest that this is a phrase we need to re-think. I started working in post-soviet and eastern ‘post-authoritarian’ European countries in early 1990. The Berlin Wall had just fallen, and I was teaching and performing at the University of Ingolstadt (then part of West Germany). The British Council invited me to travel around the then East Germany and contact some of their state theatres. I did. I met lots of fantastic people and ended up working there for a couple of decades. From the mid 1980’s I worked a lot in Spanish theatres but also with secondary and primary teachers of various subjects including History. I was interested in how schools could make their work with children more creative, less authoritarian! I discovered that classrooms and curricula had a lot in common with rehearsal rooms and scripts. And both often reflected the political and power mechanisms at play in the wider society. For example, in the 1960’s and 70’s if a child spoke Basque in a Spanish school they could, and did, get a beating from a teacher. But the same was happening in the wider society too. Where countries had recent experience or memory of authoritarian political leadership or culture one could expect to find similar authoritarian attitudes to problem solving, decision making, discipline in schools, hospitals, theatres, kindergardens, in curricula and in theatre texts!

I directed a play by Charlotte Keatley called, ‘My Mother Said I Never Should’ in Warsaw in 1995. And my theory seemed confirmed. There was a real expectation that the director would be a mini-dictator (actually, not that mini!). But that same expectation, from managers and actors alike, was not dissimilar in Spain or eastern Germany. I found that fascinating and terrifying! Someone once said to me, “Franco will not be dead until the last teacher trained under Francoism has retired from the classroom”. And I thought, “well, that could be the year 2010!” That might be unfair as many teachers in Spain were deeply resistant to Franco’s ideology. But it does raise important questions about historical legacy and how values are transmitted through education and culture through generations.

Since the late 1980’s I have lived and worked in a number of European countries. Spain, Poland, Germany, Ireland and Bulgaria, where I now live. I am European. For me Europe has made my life, and the life of my children, immensely richer. Not because we are wealthier because of the EU but because of the freedom of travel, work and study that has been a direct legacy of 1989. That freedom has been given up by the UK as a direct result of Brexit. I don’t understand how British children, no longer being able to work or study freely in 27 countries, are somehow ‘taking back freedom’. It seems someone has swallowed quite a terrifying and dangerous myth. But it is a potent one. Historical myths can lead us to surrender our own freedoms!

- What are the main (artistic – and not only) challenges while directing events as extensive as opening ceremonies for Olympic games or ECoC? Does the size (budget, too) of creations and ideas liberate you or, on the contrary, put you under an obligation?

- What are the main (artistic – and not only) challenges while directing events as extensive as opening ceremonies for Olympic games or ECoC? Does the size (budget, too) of creations and ideas liberate you or, on the contrary, put you under an obligation?

- Finding the story! Creating a useful and fascinating and helpful myth! Yes! Not all myths are unhelpful. It’s a huge task, a responsibility to be taken seriously, to find the story which interests a wide public, but at the same time does not reinforce stereotypes but creates freedom for us to think and feel about what ‘being together’ means. And that is what drew me to Kaunas in the first place. The team were clear and energised about their aims for Kaunas 2022 – and the fact that a special myth, the Myth of the Kaunas Beast, was to inform our work. Once a story, and a reason for that story, was clear then the big production and artistic decisions, budgetary implications, are so much easier.

We have lived through and continue to be impacted by Covid19. That remains a huge challenge for directing and preparing big events. Involving multiple voices in the building of a story takes lots of rehearsals, lots of listening and conversations. Rehearsals are also predicated on many people and teams coming together to work out solutions and creative proposals. And the events themselves should be carnival-like, for people to have a great time in large groups, sharing liminal moments together. Covid19 has made all three of these things, building story, rehearsals and event design, totally different for the last two years. But not necessarily for the worse! We have had a fantastic year building shows and events. Preparations have depended, more than usual, on technology and the internet. But maybe we have travelled less. Good for our skies! And when we are together it feels so special, so important. It is no surprise to any of us that during the pandemic people turned to culture across the world. Streaming services online and book sales have exploded! We, humans, are all story-telling creatures. That cannot be removed by a pandemic. Rather it is made more necessary. The question remains: Who gets to tell the stories? Are they going to help us understand the nature of the challenges we face? Or do the stories we encounter lead us towards new authoritarian myths and tales which prepare us for a new authoritarian future?

- Could you briefly compare the core ideas – or as you see them – of ECoC Wroclaw, Galway and Kaunas? Can you spot a singular vector for the project of ECoC in general, which is almost 40 years old already? I mean, do European Capitals of Culture have the same role they did in the 1980s or 1990s?

- Could you briefly compare the core ideas – or as you see them – of ECoC Wroclaw, Galway and Kaunas? Can you spot a singular vector for the project of ECoC in general, which is almost 40 years old already? I mean, do European Capitals of Culture have the same role they did in the 1980s or 1990s?

- A place, a city, Kaunas, Galway, Wroclaw are rooted, fixed and identifiable by their geographical locations. The river Corrib is among the shorted river in Europe, and as a result, one of the fastest flowing and most dangerous. The landscapes of western Ireland, Connemara, are harsh and unforgiving yet the purples in the sky and soil leave you staring in disbelief. There is also the legacy of colonialism everywhere. Have these two things impacted Galway’s sense of identity? Intensely. Yet Galway has radically changed demographically in recent decades. And Galway’s ECoC was about the way the past informs the now but also how globalised trade and communications are impacting every aspect of contemporary life. Seas, weather, languages, religions, architecture, design of urban spaces, invasions, colonial legacies all differ from country to country, city to city – yet they are all to be contended with as they are what we all share as Europeans. Wroclaw is also defined by a river, the Odra. It is also defined by legacies of war, language and population removals and arrivals. And Kaunas is defined geographically perhaps by the two great rivers, Nemunas and Neris, with their confluence creating such a magical and defining space. Is Kaunas built in this spot out of coincidence or because of this confluence? That, for me, is what European identity is about – the way we manage the legacy of multiple languages, borders, competing historical myths. As Timothy Snyder, the US historian said last year, “Europe, you are greater than your myths!”. What fascinates me about contemporary ECoC’s, those of the last 10 to 15 years, is that they seem to conclude that diversity in audiences, in communities and artists, multi-linguicism have been, and will remain, ever-present features of European life. Lithuania, Ireland, Poland, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Spain; all EU nations struggling with 20th Century legacies, looking to develop coexistence that helps us manage and thrive in a world where non-border issues now dominate all our lives. We might be from different countries but neither Covid19 nor the climate emergency respects borders, different religions, or languages.

- Are you, as a professional, learning something new while working with Lithuanian artists and communities for the Kaunas 2022 project?

- Are you, as a professional, learning something new while working with Lithuanian artists and communities for the Kaunas 2022 project?

- Kaunas is a keen and great teacher. And I am learning about human struggle, hope and joy from this perspective. On one of my trips to Kaunas, I was picked up by a young taxi driver who, in perfect English, told me about his years in Cork in Ireland. He went on to tell me the story of his family during the late Soviet period and how members of his family had been forced to fight in Afghanistan. He was a very bright and thoughtful young man who had a thousand stories that defined his European-ness. And then there are the extraordinary artists of all generations who are as comfortable working across borders and languages online as they are in referencing early 20th-century Lithuanian poets, painters, and architects. I have learnt about Lithuanian cultural trends, their interconnectedness with history and politics, neighbours, and neighbourhoods. And every day Lithuania and its artists teach me more.

- Would you agree that Kaunas has outgrown itself, its boundaries and stereotypes, during the preparation for 2022? What changes have you noticed while working with the city?

- Would you agree that Kaunas has outgrown itself, its boundaries and stereotypes, during the preparation for 2022? What changes have you noticed while working with the city?

- At the beginning of this conversation, I mentioned that my experience of Spain and Poland led me to see that authoritarianism is not something we accelerate away from but that we need to defend ourselves from – it’s a continual task in which culture, education, civic society and institutions all have a role to play. Kaunas 2022 has made an exceptional contribution to that in my opinion. And it is a key feature about ECoC’s in general, by the way. They are processes, not simply festival events. But just as festival events are defined not just by the acts on stage but by the audience who takes part, an ECoC is as much defined by the way local people, citizens and the wider community interacts with it and accept the invitation it makes to us all! Come and join in! Co-create with us! Make this your ECoC! That is what breaking down a boundary and stereotype means – to actively help in the process of making new meanings, more useful cultural works, which help us understand this world of ours. Kaunas has changed. It’s more fluid, more open, more interconnected within the city and through its understanding of its past. Kaunas is contemporary! It’s a European city with deeply European stories to share. And all this, with more work still to be done, will become the legacy of Kaunas 2022. Legacy is so important as will make sense of the investments, imaginative and financial, that have been made so far. Have you seen how Liverpool 2008 are still talking about their ECoC 22 years later?

- What is the backbone of the opening event for January? What message do you personally want to stress for the audience?

- What is the backbone of the opening event for January? What message do you personally want to stress for the audience?

- The backbone of the event is a myth! The myth of the Beast of Kaunas. The story will be extended over the other big events we are planning for May 2022 and November 2022. It’s a moment when we can come together, as a city, as a country, and kick the year off through culture. The Beast of Kaunas of course, like all myths, is not real. It’s a beautiful excuse to meet, to reflect and think! The opening weekend is an invitation to everyone. So, the show is the chance to talk together about this city, its past, present and most importantly, its future. And it is the first time in ECoC’s history that three cities, Kaunas, Esch and Novi Sad, will hold the title at the same time. What a chance to extend opportunities for audiences, communities and audiences alike to discover new things about one another?

Next year, Kaunas and Kaunas district will become one big European stage and turn the city to a place where you will not escape culture. More than 40 festivals, 60 exhibitions, 250 performing arts events (of which more than 50 are premieres), and over 250 concerts are planned to take place in 2022. It is going to be the year-long non-stop biggest co-creative festival of all. Come co-create and celebrate with us!

Full programme: https://kaunas2022.eu/en/programme/